Oliver Parker learned long ago that Manchester speaks in weather.

On good days, the city is silver—a film of light on wet brick, buses hissing past like whales. On bad days, the color drains to slate and you count your life by the squeak of your bike chain and the taste of rain. The morning of his final exam belonged to the second kind. He rode hard, backpack thumping, breath fogging his glasses, timed lights, and cut corners he’d measured a hundred times in his head. He could make it if the buses stayed where they were and the sky didn’t open.

Twelve minutes to go. He’d rehearsed this run so many times that it felt like muscle memory, like ballet in a fluorescent-lit city. He even knew where the road broke open at the curb near the bus stop—the slab that shuddered when a double-decker rolled by. He dodged it, eyes forward, mind already in the exam hall with its invigilators and rubber banded papers.

Then the city changed channels.

A man’s body turns the wrong color when it’s losing too much of something you can’t get back. Oliver saw that color on the pavement: gray-green around the mouth, the slack of a jaw, a hand with a wedding ring tucked under the edge of a bus shelter poster. He would remember that ring for the rest of his life because it caught a blunt piece of light, like a signal flare, and because everyone else on the pavement looked at the ring and kept walking.

He braked so hard that his back wheel skittered. The bike clattered to the ground. His shoulder bag swung and landed with the thud of a year’s work.

“Sir?” he said, already kneeling.

No answer. The man’s breath had that sawed-off sound, too shallow to own itself. He was maybe mid-fifties, good hair even in the rain, suit jacket slumped open, the kind of tie a person wears when it’s a habit to choose expensive things. Oliver made himself slow down. Airway, breathing, circulation. He tilted the man’s head, checked the tongue, put two fingers to the side of his neck and felt the pulse try for a rhythm. He was about to shout for help when he realized he already was.

“Call an ambulance!” he said to nobody and everybody. “Please.”

A woman in a nurse’s fleece paused long enough to thrust her phone at him. “Here!” she said, then hurried away like she owed someone an apology.

“Stay with me,” Oliver told the man. He took off his hoodie and rolled it under the man’s neck, checked his watch, began counting seconds because sometimes counting is the only strong thing you can do with your hands.

The operator asked for the street. He gave it. They asked what the man looked like. He told them. The questions were concrete and ordinary—house number, chest movement, level of consciousness—and he answered them all like a person standing in a world where the end of your degree is less important than whether a stranger lives. It felt both impossible and obvious at once.

Three minutes stretched like old elastic.

When the man’s chest hitched and steadied into something that wanted to be called breathing, Oliver’s own lungs took in more air. Sirens grew from the end of the road, swelled, and stopped. Paramedics imagined into existence from the back of a vehicle: clipboard, competence, a voice that said, “We’ve got you, sir” and meant it. One of them looked at Oliver’s hands and mistook the tremor for fear.

“You alright?”

“I’m late,” he said, and heard how stupid that sounded.

“You saved him,” the paramedic said without looking away from the pads he was placing. “That’s the story.”

He wanted so much for that to be enough.

When the ambulance doors closed, Oliver remembered the bike on the pavement like an orphaned thought. He checked his phone and watched the number mean what it meant: past the hour, past second chances, past all the negotiating you can do with a gate.

By the time he reached the exam building, the doors were shut, and the security guard had already learned the facial expression people wear when they’re about to tell you that rules are buckets without handles. “I can’t let you in, mate. The papers are out. You know how it is.”

He did. He knew exactly how it was, which is why he stood there like a person whose shape had been drawn around him in chalk.

He went home with his backpack riding too high because that’s what happens when you don’t have anything left to carry.

Oliver’s flat looked like the kind of place you rent when you’re betting against time. Ikea table with a wobble he kept meaning to fix, a corkboard stabbed with exam timetables and a single faded picture tacked just above his desk of his dad in a mechanic’s shirt wiping his hands on a rag and grinning like a person who enjoys making things run. His dad used to say, “You get one big chance and a thousand small ones. Take the small ones seriously.” He had. It didn’t feel like it mattered now.

His friends, kind people on a rotating schedule of kindness, did their best: tea, takeout, silence when needed, jokes when needed more. He let them try and failed to let himself be helped. That night, he lay on his mattress and tried to make three minutes on a pavement worth the weight of a year.

The envelope came on a Wednesday. The landlord’s mail slot made that particular metal yowl it made when something heavy and expensive landed. The letterhead looked like it belonged in a movie about rooms with carpets that smell like power: Wellington & Co. Holdings. He didn’t know the name, but his hands did that funny thing they do when they recognize the shape of a thing that changed your life.

The letter made a promise he didn’t think people could make for each other anymore. The man’s name was Harold Wellington. The words were simple in a way that made them more solid: We spoke with your university. They will administer a make-up exam. If you pass, you’ll graduate on time. I would like to thank you in person.

He read it twice, then he read it to the wall, then to the picture of his dad, and then he sat down because sitting down seemed like the most adult thing to do when the air changes.

The car came Monday, glossy and black in a way that made it the subject of its own sentence. The driver said, “Mr. Parker?” in the tone people use when they want to make sure they’re not getting something wrong. London opened around them like a second city: glass, angles, the thrum of money. Wellington & Co. rose from the pavement like it had grown there from a seed dropped by someone’s ambition.

Harold Wellington had the steadiness of someone who’d survived more than one story. He stood from a chair that looked more expensive than Oliver’s entire flat and crossed the room like a person practiced at making a space feel warmer. Up close, he had a small scar by his left eye—a reminder that the body lives in time even if your bank account doesn’t.

“Oliver,” he said. “I owe you far more than this meeting can cover.”

“It’s… good to see you upright,” Oliver said, and wished for ten seconds afterward that he had learned how to be the kind of person who says gracious things easily.

Wellington smiled as if he’d been given exactly the right line at exactly the right time. He pointed at the chair, and the room went private in that expensive way rooms do when they want to give you the impression that your life is about to be resolved. He asked about the exam, about the program he was in, about whether he preferred espresso or coffee like the kind that makes a small diner smell like hope.

“You’re an operations person,” Wellington said, listening. “You see systems. The way you built that folder—death certificate, permit, receipts—that’s how you think. That’s rare in someone your age.”

Oliver felt the words land somewhere his doubts couldn’t reach. The older man steepled his fingers like a person narrowing down a solution and said, “We choose one special intern a year. I’d like to put something on the table that aligns with your reality: sit the make-up exam and pass. If you do, the spot is yours. We’ll pay the intern salary—with hazard pay for having to put up with us.”

Oliver tried to laugh and found that his throat had sprung some kind of latch. The words came out anyway. “I don’t know what to say.”

“Start with yes,” Wellington said. “Then make us deserve it.”

He studied like a person with an engine under his ribs. The week leading up to the exam had a different gravity. He learned the library when it was empty and when it was loud. He taught himself the trick of not timing his own heart to the page. He wrote practice answers on cheap paper because sometimes it’s easier to think when the paper doesn’t look like anything valuable.

On exam day, he walked to campus in a softer Manchester that looked like it had agreed privately with itself to be kind. He sat down in a room that smelled of pencil and collective wish. For three hours, he held the shape of his future in a pen and did not let it slip.

He told nobody when he passed because saying it out loud felt like a way to make it less true. The registrar stamped things in the places where stamps go, and a woman who had worn the same cardigan the entire year gave him the sort of smile people save for a good story you’re allowed to participate in.

Wellington’s office texted, and he wrote back, and the world rotated into a new orbit like it had been waiting for him to remember where he wanted to stand. The first morning of his internship, his badge beeped at a turnstile and his shoes made the kind of sound shoes make on marble floors.

The job was what internships are when they’re real: interesting enough to feel like a promise, ordinary enough to feel like work. He moved numbers around in a system that moved trucks around in a map that moved money around in a world he had previously only rented from. He liked the fact that he could pull a dashboard and see how many shipments made it to Birmingham on time because the truth sits in numbers as well as it sits in stories.

In the third month, the story found him.

The procurement team, proud of itself for shaving pennies where dollars had learned to hide, had also shaved corners no one had signed off on. A supplier in Eastern Europe had subcontracted labor to a smaller outfit that had subcontracted ethics to nobody. The report landed on Oliver’s desk because the analyst who should have taken it left for a run and forgot to come back that afternoon. He read it, then read the attachments, then opened the file that said something it had no right to say.

He could have kept reading forever, but time is rude that way.

He took the thin folder to his mentor, a woman named Priya who was so good at her job that she had stopped needing to tell people. “This goes to Harold,” she said, and used his first name like people use the word now.

Harold listened the way powerful people listen when someone brings them a lit match. He didn’t interrupt. He didn’t move. When Oliver finished, the room behaved as if the furniture wished it could back away a little to provide more space for moral decision-making.

“Thank you,” Wellington said. He pressed a button and asked someone to bring in Compliance. Then he looked at Oliver and did something that surprised him more than anything that had happened with the ambulance that day: he asked for advice.

“What do you think we should do?”

“Tell the truth,” Oliver said, throat dry. “Stop the contract. Make it public. Fix the thing that made it possible.”

Harold put both hands flat on the table, like a vow with knuckles. “Then that’s the plan.”

The company made the announcement with the kind of language people refuse to believe until they see it: specific, not self-congratulatory, with steps and dates. It cost Wellington & Co. more money than the board liked to talk about, and it earned them more loyalty than you can buy with any amount of money.

That evening, when the last of the emails had been written by the people who do work with their names on their assignments, Harold found Oliver in the small kitchen by the lifts making tea the way people do when they’re trying to be normal after a day that wasn’t.

“You’re not here because you saved my life,” Harold said. “You’re here because you make things run through storms.”

“I thought I was the storm,” Oliver said, then realized it sounded dramatic and tried to swallow it back.

“You’re the weather report,” Harold said, smiling. “You tell us what’s coming.”

The rest of the year refused to be simple. Oliver’s mother called sometimes just to hear his voice in rooms he couldn’t afford. His friends sent pictures of their small wins. On weekends, he cycled because he trusted roads more than gyms. He put thirty pounds into a jar on his dresser each month—Emergency Oliver Fund—and adjusted his life around a future that felt less like a cliff.

The company gave him a path. Not a ladder—a path: a series of rooms where each room contained a problem and a person he needed to become. He learned how to draft emails that closed doors softly. He learned that sometimes the bravest thing you can do is ask the stupid question no one wants to say out loud. He learned that in meetings where everyone already knew the answer, the person who asks about the people downstream is the one who can live with themselves.

He also learned that the world had its own sense of symmetry. On the anniversary of the day he had missed his exam, he rode past the bus stop where the ring had caught the light. The shelter had a new poster—some streaming show about people who fall in love in kitchens—and he laughed because even cities know how to change the subject.

That week, Harold asked him to meet in a different room than usual. It had windows so tall a person could measure their life by the clouds that passed. On the table lay a folder that looked like work but wasn’t. “You said something a few months ago,” Harold began. “That day in the small kitchen by the lifts. That you counted the boy, not the hours.”

Oliver had not known that line belonged to him until he heard it given back.

“We’re going to fund something,” Harold said. “A scholarship for students who choose people over papers. For paramedics’ kids, for students who lose time doing brave things. We’d like you to help design it. And—” He adjusted his cuff not because it needed adjusting but because sometimes hands want to be busy when mouths are about to say something that changes a person’s weather. “—we’d like to name it for you. If you’ll let us.”

Oliver had read stories about moments like this. They felt like marketing or like the universe pretending to be sincere. This didn’t. It felt like two men agreeing that fewer people should have to negotiate with gates.

“It shouldn’t be my name,” Oliver said. “It should be about what it’s for.”

“Then you name it,” Harold said.

He did. They called it the Second Bell Scholarship because in Oliver’s school the bell rang twice—once to tell you to get moving and once to tell you who you were if you hadn’t. The scholarship would ring again for people who had been delayed by the right thing.

They launched it quietly in a room without balloons. The press release went out and came back in a small wave of articles written by people who understood that a different kind of story was possible. The first student to receive it was a woman who had stopped her commute to help a man who had fallen on the tracks. She wrote Oliver a letter in a careful hand that said, in essence, You made a thing that met me exactly where I stood.

When, three years after the bus stop morning, someone asked Oliver how his life had changed so drastically—how he had moved from a boy counting breaths to a man whose calendar contained meetings that moved money and ethics at the same time—he chose the smallest possible sentence.

“Because that day, I decided a human life was worth more than an exam.”

It was not a line you could put on a mug and expect to sell. It was better than that. It was something you could put on the inside of your hand like a map.

Harold, when asked in a different room by a different person with a press badge how he chose his future leaders, spoke the elevator version of a longer thing. “We don’t hire brilliance,” he said. “We hire gravity. People who make the room fall toward what matters.”

He didn’t say Oliver’s name because he didn’t need to.

When Oliver graduated, he didn’t walk across a stage because life had given him a different stage to cross. He went to the ceremony anyway, sat in the back because that’s where he likes to test the temperature of a room, and clapped for people he didn’t know because clapping is a way to be part of a collective good.

Afterward, he stood outside by a tree that had learned how to grow in the square of hard ground the city had given it. The air held the smell of wet gowns and relief. A student in a suit that needed to be ironed hugged his mother too long in the way you hug someone when you’re afraid if you let go the moment might end.

Oliver felt the old weather in his chest, that mixture of rain and light. He took out his phone and opened a note he kept for days like this. He typed a sentence and pinned it to the top: You don’t lose your future. Sometimes you just meet it earlier than you expected.

He put the phone away. A bus went past. The city exhaled. He turned his bike toward home because that’s what he still called the small flat with the wobble in the table and the jar with coins. Tomorrow, he would be in a room where people argued in sentences that contained numbers. Tonight, he would make pasta and call his mother and listen when she told him about a neighbor’s cat that had learned how to open the fridge.

At the light by the corner, he stopped and looked both ways—not because he was going to cross but because that’s what you do when you’ve learned that even the smallest pause can change a life.

Somewhere, not far in the same city, a child’s laugh rang from a bus window, bright as the ring of metal catching rain.

The weather chose silver.

Oliver chose forward.

News

She Spent Her Last $10 Helping a Stranger at the Pump. By Dawn, the Street Remembered.

The evening rain thinned to mist over the convenience store lot, slicking the concrete and sharpening the neon. Marjorie Hayes—seventy‑six,…

Boss Fired a Poor Mechanic for Fixing an Old Lady’s Car for Free — Days Later…

The sound of metal rang sharp in the garage that morning, braided with the steady hum of an air compressor…

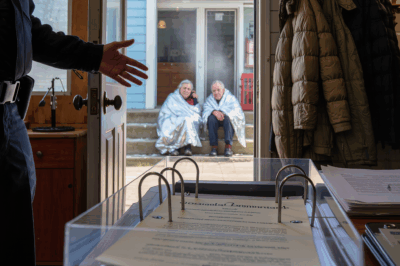

Cold on my cheeks… a wasp-buzzing bulb… something on the steps…

At 11:30 p.m. on a Tuesday, Chicago’s wind could sand a thought to bone. Frost had filmed the porch steps…

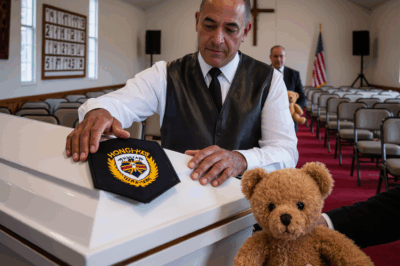

The Chapel Was Empty—Until One Small Gesture Changed the Room…

The chill that morning felt different. In Guadalajara, the wind usually smelled like metal—smoke and asphalt braided together. That day,…

She Said “Please.” The Weather Answered for Him…..The Storm Brought Her to His Door

The wind changed first. By dark, there was a stranger at the fence line and the life Diego had kept…

A Rude Manager Threw Out a Hungry Kid — Minutes Later, Bikers Took a Table

The diner smelled like fried bacon, hot coffee, and fresh rolls. For a small boy standing quietly near the door,…

End of content

No more pages to load