Part 1

My name is Connor Hayes, and I’m about to tell you how my wife’s family tried to take $16.8 million out of our marriage—and how their own prenuptial agreement became the instrument that ended up protecting me. Eleven months ago, I was sleeping in a Hampton Inn, wondering how nine years of marriage could vanish the moment real money showed up. Today, I own Phoenix Construction, a fast‑growing contractor in Austin, Texas.

The secret leverage? A prenuptial agreement that old oil money forced me to sign, thinking it would shield them forever. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me start from the beginning, back when I thought marrying into the Whitmore family was the American dream.

I’m forty‑three years old, and until eleven months ago, I thought I had life figured out. I’d spent twenty years climbing from a framer making twelve dollars an hour to Senior Project Manager at Austin Premier Construction, pulling in a steady ninety‑two thousand a year. Nothing fancy by Austin standards, but enough to keep my wife, Isabella, and me comfortable in our modest three‑bedroom near Zilker Park.

My specialty was luxury condos near the Domain—managing crews of sixty‑five, coordinating with architects, keeping million‑dollar schedules from slipping. When you’re building a twenty‑story tower, every detail matters. One mistake in the foundation and the whole thing comes down. I learned that the hard way in 2019 when a subcontractor poured concrete before the rebar inspection. It cost us three weeks and a hundred fifty thousand to fix. That lesson—document everything, follow protocol, don’t cut corners—would serve me well in the legal fight ahead.

Isabella and I had been married nine years. She was beautiful, sophisticated, and came from the kind of old Texas money that helped build downtown Austin back when oil was king. Her family—the Whitmores—owned a good chunk of the commercial real estate between Sixth Street and the Capitol. They never thought a blue‑collar guy like me was the right match for their daughter. They made that clear when they insisted I sign a prenuptial agreement before our wedding in December 2017.

“It’s just to protect family assets,” said Augustus Whitmore—Gus—in his lawyer’s office on Congress Avenue. “Nothing personal, Connor. Just business.”

I signed without much thought. Love makes you reckless. The prenup seemed straightforward: what was theirs stayed theirs; what was mine stayed mine; anything acquired together during marriage would be community property under Texas law. Simple enough, right?

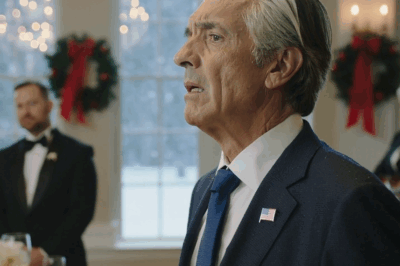

The Whitmore mansion in Westlake Hills looked like something from a television drama—eight thousand square feet of limestone raised over Lake Austin. Every Sunday dinner felt like a job interview I’d never pass. Gus collected vintage Rolex watches and club memberships with waitlists longer than building permits. His prized piece was a 1953 Submariner worth more than my annual salary. Cordelia, Isabella’s mother, curated charity galas for causes she could deduct and barely pronounce. Sebastian, Isabella’s older brother, held a Vice President title at Whitmore Properties without ever breaking a sweat.

For nine years they tolerated me. I was the construction guy their daughter married during her rebellious phase. They figured eventually I’d give up their world, or she’d give up mine. Isabella worked part‑time as a curator at Contemporary Austin, earning about thirty‑one thousand a year—more passion than necessity; her trust fund meant she never wanted for anything. We talked about kids someday, maybe a bigger house. Normal plans.

She did have one habit that grated: every week she spent fifty dollars on lottery tickets at the H‑E‑B on South Lamar. Same numbers—family birthdays, anniversaries, the date we met. “Someday these numbers are going to make us rich,” she’d say. The money came from our joint account at Austin Credit Union. Fifty dollars a week for nine years. I did the math once—over twenty‑three grand. “Babe, that’s a down payment on a lake house,” I’d tease. “Just wait,” she’d answer. “When we hit it big, you’ll thank me.” I should have paid more attention to that word: we.

November 15, 2024. A Thursday. I remember because I was reviewing blueprints for a twenty‑four‑story, forty‑five‑million‑dollar project on the east side when Isabella called at 4:17 p.m., shouting so loud I had to hold the phone away.

“Connor! Oh my God, Connor! We won! We actually won!”

I thought she meant the museum had snagged some grant. “Won what, babe?”

“The lottery! The big one! Sixteen point eight million!”

I drove home in my F‑150 so fast I’m lucky APD didn’t pull me over. Isabella was in the kitchen, dancing with a ticket in her hand, crying. Sixteen point eight million. After federal taxes—Texas doesn’t tax lottery winnings—it came to about eleven point two million. The ticket was stamped 3:42 p.m., paid with our Austin Credit Union debit ending in 7439—the same account we’d used for every ticket for nine years. For thirty minutes I believed our dreams had landed. She was on the phone with her parents, shrieking. “Mom! Dad! We did it! We actually did it!” She hugged me: “We’re rich, Connor!”

That evening the entire Whitmore family descended—Gus, Cordelia, Sebastian, even Aunt Margaret who usually pretended I didn’t exist. They brought champagne, flowers, smiles. But something felt off. The looks changed, conversations paused when I walked in. Isabella, too, felt distant, like she’d just noticed me and wasn’t impressed.

“We need to be smart,” Gus kept saying, swirling champagne. “This kind of money requires proper management.”

“Family money needs family oversight,” Cordelia added, glancing at me.

Over the next three days, Isabella’s private calls with her family stretched longer. She’d leave the room when I walked in. When I asked about paying off the house or finally starting my company, she turned evasive. “We need to think this through. My father knows people. We can’t just spend it like we won a church raffle.” Our money had become “we,” and we didn’t seem to include me.

On November 18, three days after the win, Isabella asked me to come home early. The whole Whitmore family was waiting in our living room—Gus in a Brioni suit, Cordelia with an Hermès bag, Sebastian smirking by the window.

“Connor,” Isabella began, voice stiff, “we need to discuss our… situation.”

Gus cleared his throat. “Son, this changes things. Isabella’s windfall needs proper protection.”

“Our windfall,” I said. “We’re married. Community property, right?”

Silence. “Actually,” Gus said carefully, “that’s not exactly how this works. Lottery winnings can be separate property in certain cases, especially when—”

“When what?”

Isabella looked at the floor. “Connor, I think we should… separate for a while. The money… it’s mine. I picked the numbers. I bought the ticket.”

“I want you to move out. Tonight,” she added, still not meeting my eyes.

Gus leaned forward. “The prenup protects both parties. Isabella’s lottery win is her separate property. You’re not entitled to it.”

Nine years of marriage and they were discarding me the moment real money walked in the door.

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll pack my things.” They seemed relieved at how quickly I agreed. They had no idea what they’d set in motion.

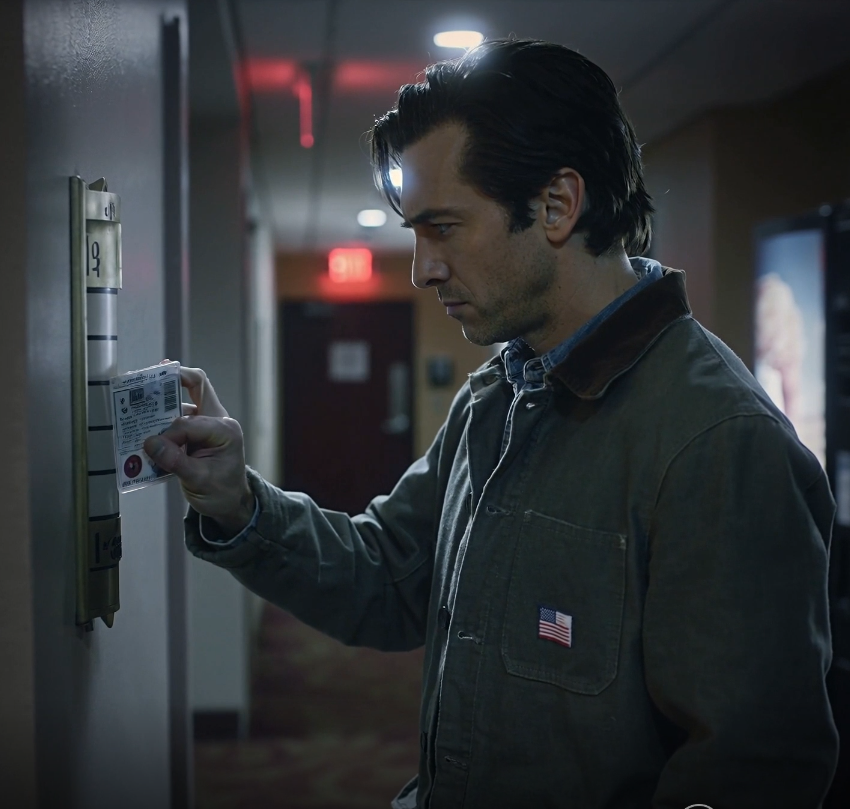

That night I checked into a Hampton Inn & Suites near the airport, room 247. Sterile walls, industrial carpet. Instead of spiraling, I went to work. Twenty years of construction taught me one thing: paperwork beats emotion. Specs beat stories. Evidence wins.

I spent three sleepless nights with a laptop, reading Texas Family Code until my eyes burned. I started with Section 3.003—the presumption that property acquired during marriage is community. Then I dug into cases: lottery winnings, separate versus community property, co‑mingling. I took notes like I was prepping for a licensing exam.

Then I built a spreadsheet: every lottery purchase Isabella had made since our wedding—every one from our joint account. I downloaded nine years of bank statements. Every transaction, date, amount. November 15, 2024: fifty‑dollar lottery purchase, debit 7439, 3:42 p.m. November 8: fifty dollars, 2:15 p.m. November 1: fifty dollars, 4:33 p.m. Week after week. All community funds. All documented.

But research only goes so far. I needed a lawyer.

Part 2

I asked around. Tommy Martinez, one of our crane operators who’d survived a brutal divorce, said, “You need Luther Blackwood. He’s tough—but he fights fair.” Luther was a former UT Law professor with twenty‑five years of high‑asset divorce experience. The consultation cost six hundred dollars; I maxed my card to pay it. His office sat on West 6th Street in a converted warehouse that whispered expensive.

He greeted me with a steady handshake. “Mr. Hayes, tell me about this prenuptial agreement.”

I slid over my copy—nine pages of legalese I’d barely read the week I signed. He scanned it, eyebrows rising.

“This is fascinating,” he said. “Their attorney was thorough—almost too thorough.”

“What do you mean?”

He tapped page four. “Section 3.7: ‘Any prizes, winnings, or awards acquired during the course of marriage shall be considered community property subject to equal distribution upon dissolution.’ Under normal Texas law, a ticket purchased with community funds is community. But even if she’d used separate money, this clause overrides that. Did you read this before signing?”

“Honestly? I skimmed it. I was in love, and they were pressuring me.”

Luther smiled for the first time. “Mr. Hayes, they handed you the blueprint to their own loss. According to their contract, you’re entitled to half of the net winnings. Section 3.003 supports it. But they’ll fight hard.”

His retainer: twenty‑two thousand. I borrowed against my 401(k) and stretched every card. Best investment I ever made.

Within forty‑eight hours of Isabella filing for divorce on November 20, the Whitmores hired Sterling & Associates—the priciest family‑law firm in Austin. Bradley Sterling himself took the case at eleven hundred an hour, known for protecting wealthy clients’ assets aggressively. His first move: letters threatening sanctions if I didn’t abandon my claim to the winnings. Thick envelopes arrived at my hotel, full of legal thunder meant to scare me off.

They misread me. I wasn’t looking for a fight, but I wasn’t going to fold.

Meanwhile Isabella lived large—and posted every moment. A Tesla Model X purchased November 28. Designer shopping. A Napa Valley weekend, first‑class flights, luxury hotels. She put eight hundred fifty thousand down on a downtown condo at The Independent—2,200 square feet with views of Lady Bird Lake—captioned: “New chapter, new home! #blessed #lottery #newbeginnings.” Perfect evidence of co‑mingling.

The court phase kicked off December 2, 2024. Sterling came out swinging—motions to dismiss, to compel arbitration, for summary judgment, for sanctions. The strategy was familiar: overwhelm me with costs. Luther stayed measured. We subpoenaed bank records showing years of lottery purchases from our joint account. We documented Isabella’s spending spree to prove she mixed lottery funds with community expenses.

Discovery was punishing. Sterling fought every subpoena, claimed privilege where there was none, and filed delays. My legal bills hit twenty‑eight thousand by January. “If this goes to trial, think forty‑five minimum,” Luther warned. “Sterling bills every call and email.”

I tightened my belt further. Job‑site lunches, gas‑station coffee. I’d rather scrape by than quit.

Then came the break.

On January 15, 2025, Luther called. “Connor, I found something. In December, Sterling filed a preliminary motion that acknowledges the lottery ticket was ‘purchased during the marriage with community funds.’ Signed under penalty of perjury.”

My heart thudded. “What does that mean?”

“It means he validated our core claim in his own words.”

By February the Whitmores were uneasy. Offers arrived. February 8: eight hundred thousand. “That’s more than you’ll see in a lifetime of construction,” Gus said on the phone.

“I’ll think about it,” I said—already decided.

February 22: one point five million. “Be reasonable.”

March 5: two point eight million. Sterling himself called. “Take it, or we’ll bury you in fees and appeals for years.”

“See you in court,” I answered.

They hired a private investigator to trail me—some ex‑cop who billed one‑fifty an hour to watch me buy screws at Home Depot and eat Whataburger. He found nothing. Next came claims that I’d been emotionally abusive, hoping to reduce any award under Texas Family Code provisions. Isabella testified I’d been controlling. But there were no reports, no medical records, no witnesses. Luther countered with phone records showing Isabella made major financial choices; bank statements showing I never restricted access; social media proving she lived freely.

“Mr. Sterling,” Luther asked during a deposition, “are we to believe someone being ‘controlled’ posts eight hundred forty‑seven public photos over nine years from galleries, wine tastings, and girls’ trips?”

Three days before trial Isabella showed up at my hotel door. She looked exhausted; the whirlwind had taken its toll.

“Connor, please. We can work this out. I was overwhelmed. My family… they got in my head.”

“Scared of what, Isabella? Sharing good fortune?”

“I’ll give you four point two million,” she whispered. “More than half. No more court. No more lawyers.”

I looked at the woman I’d loved for nine years. “It was never about the money. It was about respect. About the promise we made.” She left in tears. I almost felt sorry for her. Almost.

Part 3

March 22, 2025. Travis County Family Court—Courtroom 3. Judge Maria Gonzalez presiding. A fifteen‑year veteran of the family bench, known for thorough prep and a no‑nonsense approach. The courthouse buzzed—local news crews from KXAN, Fox 7, and the Austin American‑Statesman waited outside. “Blue‑Collar Builder vs. Old Money” made tidy headlines. I wore my best navy suit from Men’s Wearhouse—the one from our 2017 wedding. Luther suggested I spring for something pricier. I chose to be myself.

Isabella sat with her family—Gus in Brioni, Cordelia gripping her Hermès, Sebastian checking his Rolex. Sterling leaned in to whisper strategy.

Judge Gonzalez called the case. “We’re here for Hayes v. Hayes.” She nodded at Sterling.

He stood, confident, though his hands shook. “Your Honor, this is a case of a vindictive husband attempting to take money he did not earn. Mrs. Hayes selected the numbers based on meaningful family dates. She purchased the ticket with her own effort and hope. My opposing party seeks to exploit a technicality in a prenup to claim half of funds that are separate property under Texas law.”

Luther didn’t flinch. When it was his turn, he stood like a chess player watching a prewritten line unfold. “Your Honor, this case is simple. A prenuptial agreement signed in December 2017 explicitly states that any prizes or winnings during marriage are community property. Texas Family Code §3.003 supports the presumption. We also have documentation proving the winning ticket was purchased with community funds from the parties’ joint account. The defense asks the Court to ignore its own contract because they dislike the outcome. But contracts mean what they say—not what we wish they said later.”

Evidence was devastating for Isabella’s side. Luther presented bank records showing nine years of fifty‑dollar ticket purchases from our joint account. He showed how Isabella mixed the lottery windfall with community spending almost immediately: the Tesla on November 28; the Hermès trip on December 3; the condo deposit on December 15. He held up her public posts documenting it.

“Mrs. Hayes claims she always intended to keep the winnings separate,” Luther said, “yet within two weeks she mixed those funds with community expenses and documented every step.”

He even had the H‑E‑B receipt from South Lamar for the winning ticket—joint debit ending 7439 at 3:42 p.m. Sterling’s cross tried to raise intent, but intention doesn’t outweigh action.

“Intention is irrelevant when the funds are already mixed,” Luther replied. “Actions control.”

Then came the hammer.

“Mr. Sterling,” Luther said, holding a document, “your preliminary motion dated December 3, 2024, page seven, paragraph three, states: ‘The lottery ticket in question was purchased during the marriage with community funds from the parties’ joint account.’ Do you recall submitting this?”

Sterling’s face blanched. “That was… a misstatement.”

“A misstatement you signed and filed with this Court under penalty of perjury?” Judge Gonzalez asked, leaning forward.

“I misspoke,” he said. “I meant—”

“Your Honor,” Luther said calmly, “opposing counsel’s filing acknowledges the central fact. Their own record supports our position.”

The Whitmores looked rattled. Gus dabbed sweat. Cordelia shook her head. Sebastian finally stopped checking the time.

Isabella took the stand. Sterling had coached her, but the ground had shifted. Luther’s questions were clean, patient.

“You’ve testified you intended to keep winnings separate. Why did you deposit the full eleven point two million into your personal Bank of America account—the same account you’ve used to pay community expenses since 2019?”

“I… I needed somewhere to put it.”

“You have a separate frost account your husband never accessed, correct?”

“Yes, but—”

“That account had over seventy‑three thousand dollars on November 15, 2024, correct?”

“Yes.”

“So you had a place to keep money separate, yet you chose not to, and you began spending freely. Correct?”

“I… I guess so.”

“You bought a Tesla on November 28, thirteen days after deposit, for ninety‑five thousand. Did you consult your husband?”

“We were separated.”

“You filed for divorce on December 2. On November 28, you were still married. Did you discuss that purchase?”

“No.”

Luther walked through each expense: designer bags, Napa, the condo deposit. Each signed admission seated the point.

Judge Gonzalez recessed at 12:30 p.m. In the hallway, Gus approached. “Connor, this is madness. We’ll appeal. This could drag on. Cost you everything.”

“That’s your choice, Gus,” I said. “I’ve got time—and a good attorney.”

His face reddened. “You ungrateful—” He stopped short, swallowed the rest. “We welcomed you into our family.”

“No,” I said quietly. “You tolerated me. Until you thought I was expendable.”

Part 4

The afternoon session was brief. At 2:15 p.m., Judge Gonzalez delivered her ruling.

“I’ve reviewed the evidence and applicable law. The prenuptial agreement signed in December 2017 is clear and unambiguous. Section 3.7 states that any prizes or winnings acquired during marriage are community property. Texas Family Code §3.003 supports this presumption. Furthermore, the defendant’s immediate co‑mingling of the lottery funds with community expenses demonstrates recognition that the funds were not separate property.”

Isabella began to cry. Her mother gripped her hand.

“In this jurisdiction, we honor written agreements. The parties cannot now claim their own contract doesn’t mean what it plainly says simply because they dislike the result.” She looked at me. “Mr. Hayes, while the Court does not award attorney’s fees here, I am awarding you fifty percent of the net lottery winnings, totaling five point six million dollars. Mrs. Hayes, you have ninety days to liquidate assets if necessary.” The gavel fell at 2:22 p.m.

Outside, reporters circled. I ignored most questions, except one from KXAN: “Mr. Hayes, how does it feel to win?” I stood in the Texas sun and thought about the long road here. “Justice feels good,” I said.

Six months later, September 2025, I used part of the settlement to buy Austin Premier Construction from my retiring boss. Today, Phoenix Construction employs forty‑one people and focuses on attainable housing across Central Texas—starter homes, duplexes, small subdivisions in places like Del Valle and Pflugerville. Good, honest work for working families.

Isabella sold the Tesla, reversed the condo deposit, and let go of most designer purchases to meet the judgment. The bags went back. The Napa photos stayed online, expensive memories. Last I heard, she worked at her father’s real estate office in Westlake, earning thirty‑eight thousand a year and living in a one‑bedroom in South Austin. Her social feeds went quiet after trial. The Whitmores never spoke to me again, which suited me fine. When push came to shove, they showed me exactly who they were.

I heard Gus sold two vintage Rolexes to help cover the payout. Fitting. Sterling & Associates billed the family three hundred forty thousand in fees. Luther’s final bill to me was forty‑seven thousand—worth every cent.

Sometimes the best response isn’t retaliation. Sometimes it’s letting people face the results of their own choices. They drafted the contract they thought would fence me out. I had the resolve to hold them to it.

My 1985 F‑150 still runs great. Some things in this country are worth keeping. If you appreciated this story of a builder standing his ground in Austin, Texas, feel free to follow along for more. And if you’re reading in the U.S., you know this much is true: agreements matter. The Whitmores learned that the hard way.

What would you have done in my situation?

News

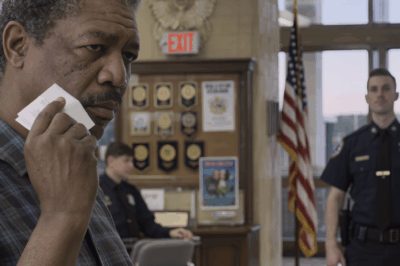

White Officer Spits on Black Man, Then Learns He’s the New Police Chief

Part 1 — The Undercover Arrival (Blue Ridge, North Carolina) It was a muggy Tuesday morning in August when Richard…

I Attended The Wedding Of My Son… and My Nameplate Said: “Low-Educated Fake Dad.”

Part 1 — The Nameplate I stood at the back of the luxurious ballroom, straightening my ill‑fitting suit. It was…

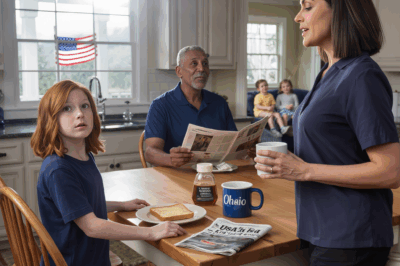

At Breakfast, Mom Said: “Your Sister’s Twins Will Take Your Room — They Need More Space To Grow.”

Part 1 — The Breakfast and the Line in the Sand At breakfast, Mom said, “Your sister’s twins will take…

They said it at my own dinner table in New Jersey—right over paper plates and a bottle of California red I wasn’t offered.

Part 1 — The Birthday Breakdown & The Decision I wasn’t expecting a celebration. It was just my forty‑sixth birthday,…

My Wife’s Lawyer Served Me Papers at Work — I Handed Him an Envelope That Ended Her Case in Court

Part 1 — The Footage, the Folder, and the First Cracks My wife didn’t just betray me. She planned to…

Judge Mocks Teenager in Court, Shocked to Learn He’s a Genius Attorney in Disguise!

Part 1 Judge Grayson thought he was sentencing a clueless teen until the defendant started dismantling the case like a…

End of content

No more pages to load