It’s been said that family is the greatest blessing in life. But sometimes, it becomes the source of our deepest wounds.

My name is Barbara Wilson, and for thirty‑four years I believed the sacrifices I made for my family would someday be returned with gratitude and love. I was wrong.

Before we go on, tell us where you’re tuning in from. And if this story touches you, make sure you’re subscribed—because tomorrow I’ve saved something special for you.

The moment I realized the true nature of my relationship with my son and daughter‑in‑law wasn’t when they forgot my birthday, or when they asked me to babysit for the fifth weekend in a row. It was when my daughter‑in‑law, Jennifer, looked me straight in the eye and said, “We think it would be best if you skipped Christmas with us this year. Thomas and Diana are hosting. And honestly, Barbara, you just don’t fit in.”

Those words shattered something inside me. After everything I had done—after the countless nights I spent awake with a sick child, after draining my retirement savings to help them buy their home, after silently paying their mortgage for three years—I was told I didn’t belong in my own son’s life during the holidays.

That was the moment I decided enough was enough. If I wasn’t “family enough” to sit at their Christmas table, then I wasn’t family enough to keep paying for the roof over their heads. What happened next changed everything for them—and especially for me.

I never expected my life to turn out this way. At sixty‑two, I thought I’d be surrounded by family, spending my retirement years gardening and spoiling grandchildren. Instead, I found myself alone in a house that felt too big, too empty—rooms full of memories that suddenly seemed to mock me.

My journey began in Oakridge, Pennsylvania—big enough to have its own hospital, small enough that everyone knew everyone’s business. I started nursing at St. Mary’s Medical Center right after school. That’s where I met my late husband, Robert, a hospital administrator with the kindest eyes I’d ever seen. We married young, bought a modest house on Maple Street, and planned for a big family.

Life, however, had other plans. After years of trying, we were blessed with one child, Michael. From the moment he was placed in my arms, I knew I would do anything for him. When he was diagnosed with severe asthma at three, I reduced my hours to care for him. Those nights—listening to his breathing, rushing to the ER at the first sign of an attack—bonded us in a way I thought was unbreakable.

Robert and I poured everything into giving Michael the best life possible. We saved for college, drove older cars, cut corners. When he showed interest in computers, we scrimped to buy him his first desktop. When he wanted coding camps, I picked up extra shifts.

Robert never got to see Michael graduate. A sudden heart attack took him when Michael was twenty. The life insurance barely covered funeral expenses and the remaining mortgage. I was devastated—but I had Michael to think about.

“Mom, maybe you should sell the house,” Michael suggested about a month after we lost Robert. “It’s too big for you, and the money could help with my tuition.”

His words stung. That house held our life with Robert. I brushed the hurt aside.

“This is our home,” I told him gently. “Your father and I worked hard for it. Besides, where would you stay during breaks? I’ll pick up extra shifts.”

And that’s exactly what I did. For three years I worked sixty‑hour weeks, taking overnight shifts no one wanted. By the time Michael walked across the stage with his computer science degree, I was exhausted—but proud.

“I did it, Mom,” he said, hugging me after the ceremony. “I couldn’t have done it without you.” Those words meant everything then.

Michael landed a tech job in Oakridge. He wouldn’t have to move away. I was overjoyed. I kept working at the hospital, where Dr. Richard Montgomery—our new chief of medicine—often told me I was the nurse he could always count on. He was a widower; we had the quiet, steady friendship of two people who had carried more than our share of long nights.

During Michael’s second year at the company, he met Jennifer Parker. Beautiful. Ambitious. From a wealthy Westfield family. Her father, Thomas, owned a chain of car dealerships; her mother, Diana, was known for elaborate charity galas.

“Mom, I want you to meet Jenny,” Michael said the first night he brought her to dinner. “She’s in marketing. She’s amazing.”

Jennifer was polite but distant. She glanced around our modest living room, eyes lingering on the outdated furniture and framed photos.

“Your home is… quaint,” she said, the tone doing most of the talking. “Michael tells me you’ve lived here your whole married life.”

“Yes,” I replied warmly, trying to bridge the gap forming in the space between my couch and her smile. “Robert and I bought it when we were just starting out. It’s not fancy, but it’s filled with love.”

Jennifer smiled tightly. “Well, that’s what matters, isn’t it? Though Michael and I have been looking at properties in Lake View Estates. Have you seen those? Gorgeous.”

Lake View Estates was the most expensive neighborhood in Oakridge. The houses started at prices I couldn’t fathom.

Six months later, they announced their engagement. I was happy for Michael, worried about the difference in expectations. I tried to be involved.

“Barbara,” Diana said during our first wedding meeting, “we’ve already reserved the Westfield Country Club and hired the top planner. We’ll handle the arrangements. You don’t need to worry about a thing.”

I offered to host the rehearsal dinner.

“Oh,” Diana exchanged a glance with Jennifer. “We’ve already booked Le Château. Thomas has a connection.”

“I see,” I said. “Is there anything I can help with?”

Jennifer patted my hand. “We know you want to contribute. Maybe you could help assemble the favors.”

I swallowed my pride and nodded. If a mother’s job was to support her child’s happiness—even when it stung—then I would do that.

The wedding was extravagant. Designer gowns, ice sculptures, a band that had once played for a minor celebrity. I felt out of place in my best dress, suddenly inadequate among the Parkers’ circle. Michael spent most of the night with Jennifer’s family, stopping by my table briefly.

“Are you having a good time, Mom?” he asked, tie loosened from hours of dancing.

“Of course, sweetheart. Everything is beautiful. I’m so happy for you.”

He looked relieved. “Jenny’s dad is talking about bringing me into the business side. Says I have potential beyond programming.”

“That’s wonderful,” I said, meaning it—even as a quiet worry took root.

After the honeymoon, they started house‑hunting in earnest. They invited me one weekend to see a four‑bedroom colonial in Lake View Estates with a gourmet kitchen and a lake view.

“Isn’t it perfect, Mom?” Michael’s eyes were bright.

“It’s lovely,” I said. “But are you sure it’s within your budget?”

Jennifer’s smile thinned. “My parents are helping with the down payment as a wedding gift. We’ve run the numbers.”

About a month after they moved in, Michael called with a strained voice.

“Mom, I hate to ask, but we’re in a bind. Property taxes are higher than expected, and with the new furniture and Jenny’s car payment—”

“How much do you need?” I asked.

“Five thousand would help us get caught up.”

I withdrew the money the next day. I’d been saving for a small condo for my own retirement, something easier to maintain. But Michael needed me. That was what mattered.

It became a pattern. Every few months: a temporary emergency. The A/C needed replacing. Jennifer’s company downsized; she needed certifications. The floors had to be replaced because she didn’t like the color. Each time, I dipped further into savings. Each time, Michael promised it was just until they were on their feet. Each time, the thank‑yous grew shorter.

Then came the biggest request. Michael sat at my kitchen table—the same table where I’d helped him with homework, where we’d grieved Robert, where we’d planned his future.

“Mom, we’re struggling with the mortgage,” he said, twisting his ring. “The rate adjusted up. Jenny’s father had business setbacks, so they can’t help. Could you… cover it for a while? Just until my promotion comes through, or Jenny finds a better position.”

I took a breath. “How far behind?”

“Three months.” He stared at his hands. “It’s just too high right now.”

I agreed. I couldn’t bear the thought of my son losing his house. “I’ll talk to Dr. Montgomery about extra hours.”

At sixty, the overnights were hard on my body. But I would manage. Michael’s relief was palpable.

“You’re the best, Mom. We’ll pay you back once we’re on solid ground.”

For the next three years, I paid their mortgage without complaint. Month after month, transfers went out. I skipped lunches at the hospital, postponed repairs on my own home, let my car go without maintenance, declined invitations that cost money. Sunday dinners with Michael and Jenny became monthly, then occasional. Phone calls grew shorter.

“The new sectional is gorgeous,” I said on one visit, glancing at the clearly expensive piece.

“It’s from the designer showroom in the city,” Jennifer said lightly. “We decided to treat ourselves a little. Mental health is important, you know.”

I bit my tongue, thinking of the leaky faucet I couldn’t afford to fix.

That evening, I overheard Jennifer on the phone with her mother: “I know, Mom. It’s exhausting having to include her in everything, but Michael feels obligated. At least she helps out financially.”

Helps out. I was paying their mortgage.

The real turning point came the week before Thanksgiving. I’d battled a persistent cough for weeks, pushing through shifts despite fatigue. Dr. Montgomery caught me leaning at the nurse’s station, short of breath.

“That’s it, Barbara,” he said firmly. “I’m ordering a chest X‑ray right now.”

Pneumonia. Complications from exhaustion and a weakened immune system.

“You need rest,” he insisted. “Complete rest. Medical leave for at least four weeks.”

I protested, thinking of the mortgage due in two weeks. He was adamant: “Your health comes first.”

That night, I decided I would call Michael, explain the situation, and ask them to handle the mortgage for a month or two while I recovered.

Jennifer answered. “Barbara,” she said coolly. “Michael’s in a meeting. Can I take a message?”

“It’s important, Jenny. I need to talk to him about the mortgage payment.”

A pause. “The mortgage payment. What about it?”

“I’m on medical leave. Pneumonia. I won’t be able to work extra shifts for a while. I was hoping you and Michael could cover the next payment until I’m back on my feet.”

Silence stretched.

“Jenny, did you hear me?”

“I heard you,” she said, her voice suddenly hard. “So you’re saying you won’t be sending the money this month?”

The way she phrased it—like an obligation, not a sacrifice—stung.

“I can’t, Jenny. I’m ill. The doctor says—”

“We’re counting on that money, Barbara,” she cut in. “We have plans. We’ve already booked our ski trip over Christmas.”

Cold realization washed over me. They had money for a ski vacation—but not for their mortgage.

“I’ve covered your mortgage for three years,” I said quietly. “I think you can manage for one month while I recover.”

She gave a short, dismissive laugh. “Right. Because that makes up for everything Michael did for you after his father died. How he stayed local because you couldn’t handle being alone.”

“That’s not true,” I said, the words barely above a whisper. I had worked extra shifts to keep him in college and encouraged him to follow his dreams.

“Look,” she said, patience forced. “We all know you’ve been helping because you wanted to be involved. That’s fine. But don’t use your health as leverage.”

I was speechless.

“I’ll talk to Michael tonight,” I managed. “Please have him call me.”

He didn’t call that night. Or the next. When he finally did, he sounded rushed and defensive.

“Mom, Jenny told me. I’m sorry you’re not feeling well, but we really need that payment. We’ve committed to hosting a pre‑Christmas dinner for Jenny’s colleagues, and we ordered new dining room furniture.”

“I’ve been paying your mortgage for three years,” I said, steady despite the ache in my chest that wasn’t just pneumonia. “Three years of extra shifts, skipped meals, postponed repairs. I’m asking for a short break while I recover.”

Silence.

“So you’re keeping track?” he said finally. “I thought you were helping because you wanted to—not because you expected something.”

The words landed like a blow. When had my son become someone who could speak to me like this?

“I expect respect,” I said, voice breaking. “And some concern for my health.”

“Of course I’m concerned,” he said, but his tone told a different story. “It’s just bad timing.”

“Obligations more important than your mother’s health?”

He sighed. “Let’s not make this dramatic. Maybe we can send you half this month.”

“Don’t bother,” I said, a strange calm settling in. “I’ll figure it out.”

After we hung up, I sat in my silent house and saw my situation clearly. I had given everything to a son who viewed my sacrifices as obligations. I had emptied my savings to maintain his lifestyle while neglecting my own needs. I had worked myself into illness for people planning ski vacations while I couldn’t afford to fix a faucet. Something had to change—and it had to start with me.

The next day, weak but resolute, I made two calls. First, to my bank to stop the automatic transfer. Second, to my old friend Grace Thompson, the retired teacher who kept inviting me to the community center.

“Barbara Wilson,” she said warmly. “To what do I owe this pleasure?”

“Is your book club still open?” I asked, surprised by the lightness in my own voice.

“Always. Thursdays at the library. But aren’t you usually working then?”

“Not anymore,” I said. “I’m making some changes.”

As I recovered over the next two weeks, texts from Michael accumulated: Where was the transfer? Had the bank made a mistake? I ignored them and focused on getting well. I read books that had gathered dust for years, invited Grace for tea, called my sister Linda in Ohio.

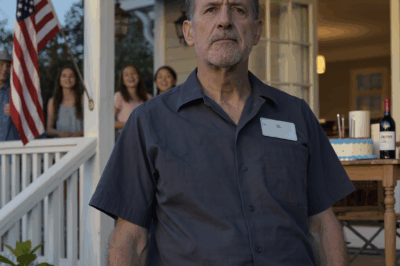

The day before Thanksgiving, Michael showed up at my door, harried and hollow‑eyed.

“Mom, the bank says the transfer was canceled.”

“It wasn’t a mistake,” I said calmly, letting him in. “I canceled it.”

“What? Why would you do that?”

“Because I’m no longer able to pay your mortgage. I’m focusing on my health and future.”

Color rose in his cheeks. “You can’t just decide that without warning. We have commitments based on that money.”

“Like your ski trip?” I asked quietly.

He looked momentarily ashamed, then rallied. “We work hard. We deserve a vacation.”

“And I deserve to retire someday. To live without exhaustion. To be treated with respect by my son and daughter‑in‑law.”

“This isn’t like you, Mom. You’ve always been there for me.”

“I always will be—emotionally. But financially, you and Jennifer need to stand on your own feet now.”

“Fine,” he said, standing abruptly. “We’ll figure it out ourselves. But don’t expect us to rearrange our lives to include you when you’re being this selfish.”

Selfish. The word hung in the room long after he left.

Thanksgiving passed at the community center with Grace—mashed potatoes, simple kindness, no eggshells to tiptoe across. For the first time in years, I enjoyed a holiday meal without tension. Peace crept in where panic had lived.

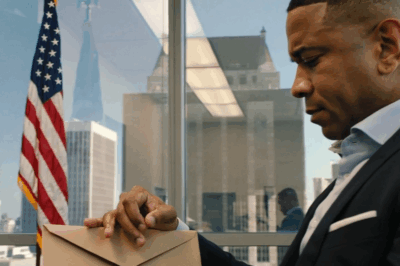

The Monday after, I met Martin Goldstein, the lawyer who’d helped with Robert’s estate.

“Tell me what’s going on,” he said.

I told him everything: the three years of mortgage payments, the pneumonia, the holiday exclusion.

“So,” he summarized, “you’ve been paying directly to their lender. No written agreement with your son?”

“That’s right.”

“How much have you paid in total?”

“One hundred twenty‑six thousand.”

His eyebrows shot up. “Substantial. Without a written agreement, a court could view it as a gift. We could argue an implied contract, but litigation would be costly and painful. The most practical option is what you’ve already done—stop paying and document everything.”

He hesitated. “One more thing. If they default on anything you cosigned, you’re exposed.”

My stomach flipped. “I’m a co‑signer on a home‑equity line of credit they took last year. Fifty thousand. Jenny said it was for improvements.”

“Check it immediately,” he said. “If they’ve drawn it, consider paying it off to protect your credit.”

At the bank, the representative pulled up the account. “Current balance: $48,622,” she said, turning the screen. “Last withdrawal: $12,000 on November 15.”

Just before they told me I wasn’t welcome for Christmas.

“I’d like to pay off the balance and close the account,” I said. My voice was steadier than I felt.

Two hours later, it was done—penalties and all. I drove home strangely calm. I had sacrificed most of my remaining savings to protect myself from my own son’s decisions. The pain was so profound it looped into numbness.

That evening, I totaled my finances. After closing the line, I had about $20,000 left in accessible savings—barely a year of modest expenses if I stopped work entirely. My pension would start at sixty‑five. The equity in my house was substantial, and I had hoped to leave it to Michael someday. The irony wasn’t lost on me.

My phone rang again. Michael.

“Mom, the payment was due yesterday. Are you sending it or not? If this hits our credit—”

“I won’t be making any more mortgage payments,” I said evenly. “I’m focusing on my own security now.”

“You what? Why would you do that?”

“I was a co‑signer. I couldn’t risk my credit.”

“We weren’t going to default. We just needed flexibility until after the holidays.”

“You withdrew $12,000 two weeks ago,” I said softly. “Was that for the ski trip? Or the new dining room furniture?”

He was silent, then defensive. “We needed to entertain. It’s important for Jenny’s career.”

“More important than your mother’s financial security? More important than basic respect?”

“You’re twisting everything.”

“I’m stating facts. I’ve supported you well into adulthood. I’m stepping back. How you handle your finances is up to you.”

“So that’s it. You’re cutting us off.”

“I’m setting boundaries.”

The conversation ended with him upset—and with me unwilling to bend.

The next morning, Jennifer texted. “Michael told me what you did. Paying off the HELOC without telling us was controlling. We had plans.”

I marveled at the logic required to frame my paying off a debt I was legally tied to as manipulation. I didn’t respond. Instead, I spoke to Dr. Montgomery about a reduced schedule. Three days a week. Day shifts. Less pay, more peace.

He studied me. “May I be frank, Barbara?”

“Of course.”

“I’ve been worried. You give so much and ask so little. The hours you’ve been working aren’t sustainable. Take the admin role. Rest.”

I accepted. He mentioned the hospital Christmas party on the twenty‑third and hoped I’d attend. I said I would.

Two weeks later, the distance helped me see the pattern: I had been enabling their lifestyle while being edged out of their lives—except when they needed money. The doorbell rang one evening. Thomas Parker stood on my porch in a cashmere coat.

“Mrs. Wilson,” he said. “May I come in? There’s a matter to discuss.”

Inside, he remained standing, posture crisp. “I understand you’ve withdrawn financial support from Michael and Jennifer’s household. The timing—so near the holidays—is unfortunate.”

“I’ve decided to focus on my own security,” I said. “They’re capable adults.”

“Be that as it may, your decision has created hardship. Jennifer tells me you paid off and closed a line of credit they were relying on.”

“I was a co‑signer. I protected my credit.”

He waved a hand. “Legally, perhaps. But surely you understand the position this puts them in socially.”

There it was: the real concern.

“What exactly are you asking, Mr. Parker?”

“A compromise,” he said smoothly, producing a checkbook. “If you resume mortgage payments temporarily—just until after the new year—I will compensate you for the inconvenience. Think of it as a consulting fee. You help us maintain appearances through the season, and I compensate you. A simple business arrangement.”

I stared at him. A wealthy man who had never once invited me to his home was offering to pay me to keep paying my son’s mortgage.

“I’m not interested in being paid to support my own child,” I said quietly. “If you’re concerned, help them directly.”

“That’s not how we do things in our family,” he said. “We believe in independence.”

The irony almost made me laugh. “Independence facilitated by a sixty‑two‑year‑old nurse working overtime?”

His face hardened. “I see this isn’t productive. I’ll tell Michael and Jennifer to make other arrangements.”

“That would be best.”

At the door, he paused. “Many parents would be grateful their child married into a family of our standing. The connections alone are invaluable.”

“Many parents would expect basic courtesy and respect, regardless of standing.”

He offered no reply. He left. I leaned against the door, heart pounding. More than anything, I realized: this was how they all viewed me. Not as a person. As a resource. An inconvenience when I failed to perform. A social embarrassment to be managed and excluded.

I made tea and stared at the red circle around Christmas Day on my calendar. Doubt rose like steam. Had I done the right thing? Should I have eased them into independence? Was I punishing them for excluding me?

The kettle whistled. Facts steadied me: I had worked myself into pneumonia. I had depleted savings. I had been told I wouldn’t “fit in” at Christmas. I wasn’t punishing anyone. I was finally treating myself with the dignity I’d long given away.

The phone rang. Michael.

“Did you refuse money from Thomas Parker?” His voice was tight.

“I refused to be paid to resume paying your mortgage.”

“Do you have any idea how humiliating that was for us?”

“If you’re embarrassed, be embarrassed that your father‑in‑law had to intervene in your finances—not that I refused to be bribed.”

“He was trying to help, and you threw it back in his face. You’re going to ruin our holidays, our standing—everything.”

“Michael, if our situations were reversed—if I expected you to work extra hours to pay my bills and then excluded you from family gatherings—how would you feel?”

“That’s different. Parents are supposed to help their children.”

“Adult children are supposed to become independent,” I said gently. “And to treat their parents with respect. Not as ATMs.”

A long silence.

“Fine,” he said at last. “Keep your money. Stay home for Christmas. I hope it’s worth it.”

The line went dead. Tears came—grief for what had been, clarity for what must be.

The next days filled with small, steady choices: I confirmed I’d attend the hospital party. I accepted Grace’s invitation for Christmas dinner. I called my sister. I decorated a small living tree for my window. A neighbor, Ellen Walsh, helped me hang lights. We made hot chocolate and—like girls—planned a spring garden club.

At the hospital party, Dr. Montgomery—Richard—introduced me around. People knew my work. They remembered my steadiness on hard nights. The CEO’s gift was a leather‑bound journal with my initials and a spa card. The journals, Richard confessed later, had been his idea. “You once told me you used to journal,” he said. “Maybe it’s time again.”

In the parking lot he asked, “There’s a chamber concert next weekend. Would you come with me?”

I blinked. “Are you asking me on a date, Richard?”

“I suppose I am.”

“It’s unexpected,” I said. “But yes.”

The concert was beautiful. Dinner afterward was gentle, easy. He listened without prying; I spoke without oversharing. When he walked me to my door, he kissed my cheek and said, “Merry Christmas, Barbara.”

I went to bed with the flutter of possibility in my chest.

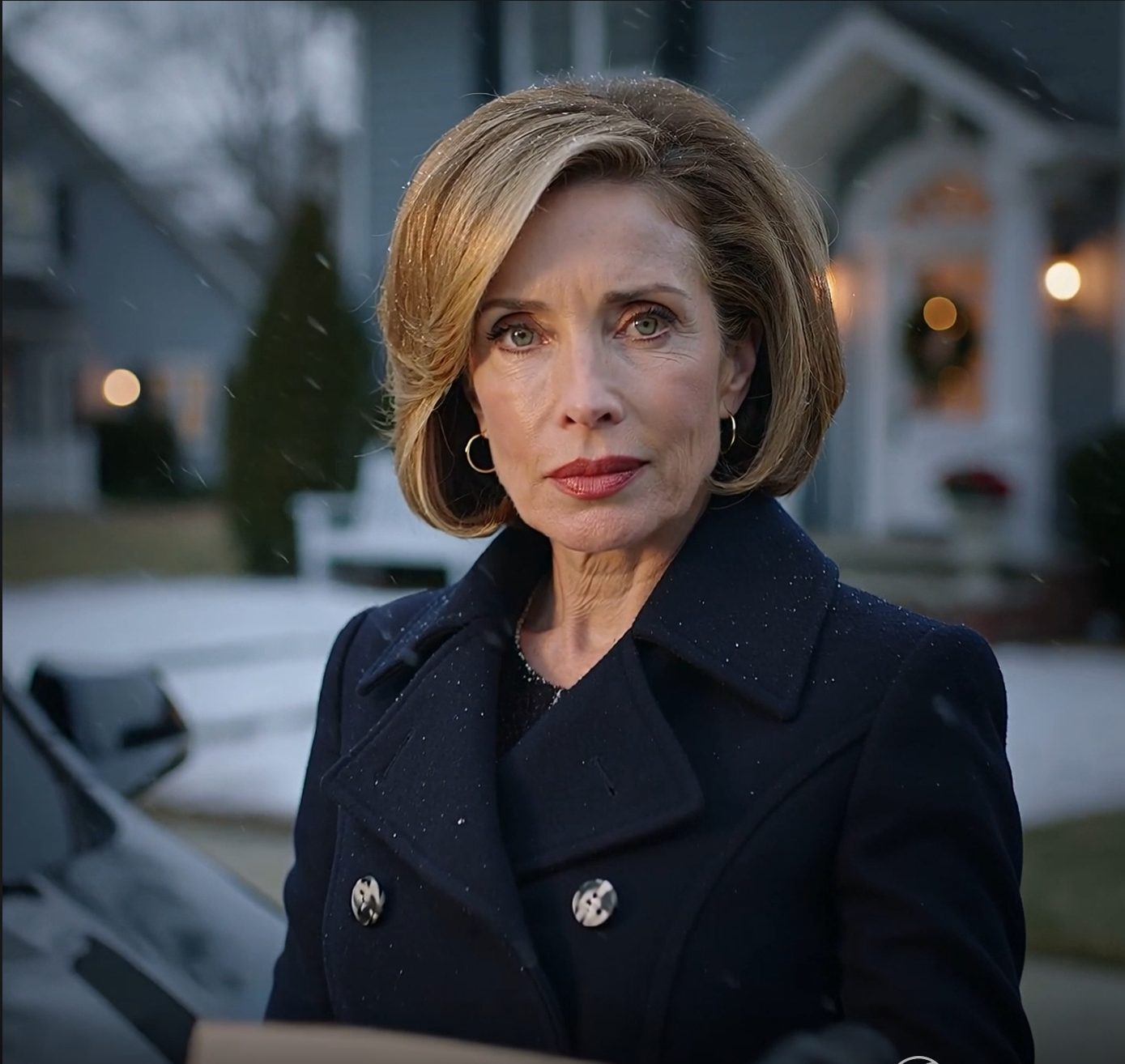

The next morning, Jennifer called. Her voice was tight. “I think we need to talk. In person.”

“At the café on Main, noon,” I said.

“Perfect.”

When I arrived, she looked tired. She leaned forward.

“Michael doesn’t know I’m here,” she said. “And I’d prefer he didn’t. I have to ask you something—and I need you to be completely honest, even if it hurts.”

“All right.”

“Did you know about the gambling?”

The question knocked the breath from me.

“Gambling?” I said. “What gambling?”

She studied my face and exhaled. “You really didn’t know.”

My world shifted on its axis.

“Tell me,” I said.

…

Jennifer studied my face and seemed to sag with relief.

“You really didn’t know,” she said. “I was afraid you might have been covering for him.”

“Covering what?” I asked gently. “Jennifer, please—tell me everything.”

She wrapped both hands around her cup as if it might warm more than her fingers.

“I found out two years ago,” she said. “Our card got declined at dinner in downtown Pittsburgh. When I checked the account, there were pages of charges—online betting sites, poker rooms, sports books. He swore it was a lapse. He promised to quit.”

She gave a humorless laugh. “Maybe he did for a while. Then about eight months ago, the pattern started again. He got secretive, started using accounts I couldn’t see. Cash advances. The works.”

I felt the floor tilt beneath me. The late‑night ‘work sprints,’ the ‘unexpected bills,’ the urgency that always seemed to arrive right before I transferred money—it all snapped into focus.

“And the money I sent?” I asked quietly. “The line of credit I cosigned?”

She looked away. “Some went to real bills. A lot didn’t.” Her voice dropped. “I’m sorry, Barbara. I should have told you sooner. I was too proud. And I was scared.”

“How bad is it?”

“Bad,” she said, meeting my eyes. “The mortgage is four months behind. Foreclosure notices have started. He opened another home‑equity line without telling me. The cards are maxed. My car is close to repossession.”

I pressed my palm to the table to steady myself. In the window behind Jennifer, snow blew sidewise along Main Street. Families hurried past in bright scarves, bags of gifts swinging from their arms, the way small American towns look the week of Christmas.

“Does he admit there’s a problem?” I asked.

“He says he has a system,” she said softly. “That he’ll win it back. Last night he lost five thousand at a casino out past the state line.”

Anger rose—clean and clarifying. Not at Jennifer. At the lies that had colonized my son’s life.

“What are you going to do?” I asked.

She startled me with her answer. “Therapy,” she said. “For me. I need to understand why I enabled this. I’ve booked an appointment. And I’m seeing a financial counselor. I’ve started looking at apartments. Small ones. Somewhere my parents won’t casually drop by.”

I reached across the table and covered her hand. “Whatever you decide, I’ll help you stay safe. That includes peace of mind.”

Her eyes brimmed. “I’ve been wrong about a lot of things,” she said. “About you, especially. I’m sorry for the way I treated you—the comments, the exclusion.”

“Thank you for saying that,” I said. “It matters.”

We left the café with a plan simple enough to hold. She would gather documents. I would be a quiet place to land if she needed one. Neither of us knew how soon that would be.

Christmas morning broke crisp and blue over Oakridge. The kind of cold that makes the air ring. At 8:00 on the dot, Jennifer knocked on my door with a small roller bag and eyes that showed she hadn’t slept.

“Thank you for seeing me today,” she said. “Michael found out we met. He got… volatile.”

“Come inside,” I said, stepping aside. “You’re safe here.”

In the kitchen, I poured coffee while she spoke in low, careful sentences.

“He said I needed to ‘fix’ things with you,” she said. “That if I apologized enough, you’d start paying again. When I said that wasn’t happening, he started blaming me—for everything. He knocked dishes off the counter. I waited until he left and packed a bag.”

“Do you want to stay here a few days?” I asked.

Relief softened her face. “If it’s really no trouble.”

“The guest room is small, but it’s yours.”

I texted Grace to reschedule our plans. She insisted she’d bring dinner to us instead—“No one should be alone on Christmas,” she said, a Pennsylvania angel in a wool coat.

At noon, the doorbell rang. Michael stood on my porch, coat unbuttoned against the cold, jaw tight. The wreath glowed behind me like a small sun.

“Where is she?” he said. “Is Jennifer here?”

I stepped onto the porch and pulled the door mostly closed behind me.

“Michael,” I said evenly, “this isn’t the way.”

“So she is here,” he said, voice rising. “She’s turned you against me. Filled your head with stories.”

“No one’s turned me against you,” I said. “But Jennifer asked for space. I’m going to respect that, and so are you.”

He laughed—brittle and wild. “Space? She’s hiding from the mess she helped create. Did she tell you about the furniture? About her cards?”

“Michael,” I said gently, “you need help. Professional help.”

“I don’t have a problem,” he snapped. “I have investments that haven’t paid yet. Temporary setbacks. That’s not an addiction.”

“Are the ‘investments’ the reason you were at a casino past the state line last night?” I asked.

He flinched. Anger surged to cover it. “She’s been spying on me now?”

“She told the truth,” I said. “That’s what happens when people stop being afraid.”

He moved to push past me. I planted my feet.

“This is my house,” I said. “You’re welcome to come in when you’re calm. Not like this.”

“You’d call the police on your own son,” he said, incredulous, when I didn’t move.

“I don’t want to call anyone,” I said. “But I will if I have to keep people safe.”

We stared at each other, two outlines in winter light. Somewhere down the block, a child whooped at a new sled. A flag on the post office across Maple Street hung still in the cold.

His shoulders sagged first.

“Fine,” he muttered. “Tell Jennifer this isn’t over. There are legal and financial realities she hasn’t considered.”

“Threats won’t help you,” I said. “Treatment might.”

He turned, then hesitated—suddenly young, suddenly lost. “Merry Christmas, Mom,” he said, voice small. “I’m sorry it’s like this.”

“I love you,” I said. “I always will. But I can’t support choices that hurt you—or anyone else.”

When I closed the door, Jennifer stood at the bottom of the stairs, one hand on the banister.

“I heard,” she whispered. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s not your fault,” I said. “He has to choose a different path. We can’t choose it for him.”

She nodded, eyes shining. “Did you mean it about calling the police?”

“Yes,” I said simply. “Boundaries keep love from turning into damage.”

At four, Grace arrived with half a holiday meal balanced in her arms and Ellen with the rest. An hour later, Dr. Richard Montgomery knocked with a bakery yule log and a bottle of sparkling wine.

“I thought we might celebrate the simple fact of being together,” he said, stepping into my warm, crowded kitchen.

We ate around my small dining table—pot roast, mashed potatoes, green beans with almonds, Grace’s famous rolls. Conversation moved in gentle circles: books, music at the university, the ridiculous synchronized light display on Cedar Street, Ellen’s latest misadventures with online dating in her bright red scarf.

Jennifer was quiet at first, then began to relax, laughing at Ellen’s stories.

“You should have seen this one fellow,” Ellen said, gesturing with her fork. “Profile said ‘high‑energy fitness guy.’ He arrived in sweatpants that had never seen a gym.”

Laughter loosened the tightness in all our chests.

After dinner, Jennifer asked if she could use the den.

“I think I’m ready to call my parents,” she said. “They need to hear it from me.”

“Take all the time you need,” I said, opening the door for her. “You’re not alone.”

She emerged twenty minutes later, eyes red but steadier.

“They’re coming tomorrow,” she said. “They were shocked. But supportive. My dad said he was proud of me for telling the truth.”

When everyone had gone and Jennifer went to the guest room, I sat on the couch in the quiet house that no longer felt empty. Snow ticked softly at the windows. The small living tree glowed in the front window like a lighthouse for second chances.

Three days later, I would learn just how quickly a life can pivot when the truth finally walks in the door. But that night I let myself rest in something I hadn’t felt in a long time: safety.

The phone vibrated on the coffee table—Michael’s name lighting the screen and then going dark when I didn’t reach for it. A minute later, a text appeared.

Mom, can we talk tomorrow? It’s important.

I stared at the message, at my reflection in the black glass—sixty‑two, tired, but no longer willing to disappear inside other people’s emergencies.

I typed three words and set the phone face‑down:

We can talk.

…

I didn’t sleep much. The house was quiet, the kind of quiet that hums—refrigerator, vents, the soft tick of the thermostat. Somewhere after midnight a plow rolled down Maple Street and pushed the snow into crisp ridges at the curb.

At 8:30 a.m., I texted Michael: Noon. Café on Main. Public place.

He wrote back in seconds:

Okay.

Jennifer came down in sweats and a cardigan, hair pulled into a low knot. We ate toast with orange marmalade at the counter like two people who had done this a hundred times.

“You don’t have to go,” she said.

“I do,” I said. “Not to fix anything. To be clear.”

The café was half full—holiday stragglers, a couple of college kids home from Penn State, a mail carrier on break. I picked a table by the front window where the light was clean and impossible to lie under.

Michael arrived late. He looked like he’d been up all night—shadowed eyes, the defensiveness that follows a poor decision.

“Mom,” he said, sliding into the chair. “Thanks for meeting.”

“Michael,” I said. “We’ll keep this simple.”

He nodded like he was bracing.

“I’m not resuming payments,” I said. “I’ve protected my credit. I won’t cosign anything else. I love you. I am saying yes to every healthy thing—meetings, treatment, accountability. And no to every unhealthy thing—secrecy, pressure, emergencies that show up like clockwork.”

He stared out at Main Street. “You make it sound so—binary.”

“It is,” I said softly. “The in‑between is where we’ve been living for years. It’s swallowed me whole.”

“I can fix this,” he said, the familiar bravado that used to be adorable when he was nine and insisted he could build a treehouse alone. “I just need time.”

“Fixing starts with telling the truth,” I said. “Not to me. To yourself.”

He swallowed. “Jenny talked to you.”

“She did,” I said. “She told me enough to understand the shape of it. She didn’t tell me everything.”

He laughed without humor. “There’s always more.” He rubbed his jaw, buying seconds. “You always assumed I was so responsible. That I would do the right thing. I wanted that to be true more than anyone.”

“You can still make it true,” I said. “But it starts differently than you think.”

He squinted at the window glass as if the right angle could show him another version of our lives.

“What do you want from me?” he asked at last.

“Three things,” I said. “A professional evaluation by someone who understands gambling. Full financial transparency with a counselor. And no more debt in my name or Jennifer’s without explicit consent.”

He bristled at the last one, even though it was the easiest ask. “I’m not a criminal.”

“I didn’t say you were,” I said. “I’m saying we’re done with side doors.”

His eyes flashed, then dimmed. “If I do those things—will you help with the mortgage until spring?”

“No,” I said. “That’s not a bridge I can build for you anymore.”

He leaned back, exhaling. “I don’t even know where to start.”

“At the beginning,” I said. “There’s a Tuesday night meeting at First Presbyterian on Walnut at seven. You walk in, sit down, and when it’s your turn, you say, ‘My name is Michael.’”

He picked at a paper napkin until it dissolved under his fingers.

“I miss Dad,” he said suddenly, voice breaking around it. “He’d know what to do.”

“He’d tell you the truth,” I said. “And then he’d sit beside you while you did the hard thing.”

We left it there—not fixed, not wrecked. Michael hugged me in the parking lot like he was trying to remember how. When he pulled back, his eyes were wet.

“I’ll call you,” he said.

“I’ll answer,” I said. “When I can.”

Back home, Jennifer’s parents’ SUV sat at the curb—a gleaming, winter‑salted monument to Westfield success. Thomas and Diana stood on my walk, bundled, faces careful. Jennifer opened the door before I could reach it and folded into her mother the way a child folds when the strong front finally cracks.

“Jennifer,” Diana whispered, smoothing her daughter’s hair. The Parker composure held, but barely.

Thomas reached for my hand. “Barbara,” he said. “Thank you.”

He had never said my name like that—without the slight elevation, without the performance. For the first time since I’d known him, his eyes were simply human.

We talked at the kitchen table because all important conversations in American houses happen at kitchen tables. I poured coffee. Diana produced a small notepad from her bag like a general. Thomas said very little. He listened.

Jennifer told them the truth, the whole of it, without flinching. The online accounts. The cash advances. The late mortgage. The line of credit. The casino. She didn’t spare herself—the avoidance, the furniture bought on credit because appearances were a wall she had learned to live behind.

Diana’s face changed gradually, like weather moving over water—surprise, hurt, grief, resolve.

“First,” she said when Jennifer finished, “you will not carry this alone anymore. Second, I’m sorry for the ways I modeled the wrong priorities. Third, we will do this properly.” She clicked her pen like a gavel. “We’ll retain a financial counselor today. We’ll speak to an attorney about separation options that protect you. We’ll arrange for an evaluation if Michael agrees. And we will support you if he does not.”

Thomas cleared his throat. “I grew up in a house broken by this,” he said quietly. “My father swore he had a system right up until the bank took our store. We will not repeat that history.”

He turned to me. “I owe you an apology.”

“You don’t,” I said.

“I do,” he insisted. “For coming to your home last week as if this were a negotiation. It wasn’t. It was cowardice. I did not want to look under the rug.”

Something unknotted a fraction inside my chest. “Thank you,” I said. “I accept.”

By afternoon, we had an appointment with a counselor in the city, a referral from Diana’s friend who ran a nonprofit that supported families through financial crises. We scheduled a consultation with a family law attorney for Jennifer—to understand paths and protections. None of it was dramatic. None of it was easy. It was work. The kind you do when you finally stop pretending the house isn’t on fire.

That evening, the four of us carried boxes to Jennifer’s car—paperwork, a few outfits, a jewelry box from her grandmother, two framed photos. She insisted on leaving the rest for now, a practical decision that felt like choosing which ribs to protect.

At the curb, Thomas touched my arm. “We’ll make sure Jennifer is safe,” he said. “If you need anything—anything at all—you call me.”

“I will,” I said. And I meant it.

When their taillights disappeared, I stood on the porch and watched the breath leave me in little clouds. The neighborhood was quiet in that post‑holiday way—lights still up, packages long opened, the promise of a new year hanging like the cold, bright moon.

Inside, I sat with my leather‑bound journal and wrote three lines:

I will not carry what is not mine.

I will tell the truth kindly.

I will not disappear.

Two days later, I was back at the hospital for my first official week in the administrative role. The rhythm was different—emails, budgets, schedules. My legs ached less at night. My head ached more around spreadsheets. Richard stopped by my desk at noon with two coffees and a smile that made a few nurses down the hall raise their eyebrows in delighted speculation.

“Walk?” he asked.

The sky over Oakridge was the color of pewter. We circled the small park across from St. Mary’s where children climbed a play structure shaped like a fire engine and a bronze plaque honored hospital donors. Richard told me about a cardiology fellowship candidate from Michigan. I told him about the Parker kitchen summit and the list on Diana’s notepad.

“You’re doing the right things,” he said, bumping my shoulder with his. “The hard things are right more often than not.”

“My heart still hurts,” I admitted.

He nodded. “Healing and hurting aren’t opposites. Sometimes they hold hands for a while.”

That night, Michael called just before nine.

“I went,” he said without preamble. “To the meeting.”

I closed my eyes. “How was it?”

“Terrible,” he said. “And good. They were so… normal. A retired state trooper. A woman who owns a bakery. A guy who sells HVAC systems. They all said the same things I say. They all laughed and then looked like they wanted to cry. I hated it. I might go back.”

“I’m proud of you,” I said. “For walking in the door.”

Silence stretched and softened. “Mom?”

“I’m here.”

“Are you happy?” he asked, so suddenly it caught me wide open.

I looked around my small, old kitchen that smelled like Earl Grey and lemon oil, at the little living tree still in the window, at the hospital pin on the counter by my keys.

“I’m becoming happy,” I said. “That counts.”

“I don’t know how to be that,” he said, a boy again for a heartbeat.

“You’ll learn,” I said. “One honest day at a time.”

Weeks moved the way winter weeks move—slow and exacting. Jennifer met with the counselor and began building a clean ledger of her life. She found a one‑bedroom close to her new job in the city—walkable, sunlit, nothing like the curated perfection of Lake View Estates. Diana visited on Saturdays with soup and practical advice. Thomas and I learned how to speak plainly to one another. It felt like a small miracle each time we did.

Michael called every few days. Sometimes he sounded clear, sometimes brittle. He went to meetings. He slipped and admitted it. He went again. He found a sponsor—a man named DeShawn who owned the HVAC company and said point‑blank on their first coffee, “I will not be more invested in your recovery than you are.”

On a Sunday in January, I hosted dinner—nothing fancy, a roast chicken with lemon, baby potatoes, a salad with cranberries and walnuts. Ellen arrived carrying a pie, Grace a loaf of bread still warm from the oven. Richard brought tulips—stubborn, bright, the kind that remind a house spring exists. Jennifer came late straight from her apartment hunt, cheeks pink from the cold, and took the chair to my left as if it had always been hers.

Midway through the meal, my phone buzzed with a number I didn’t recognize. I almost ignored it—then saw the tiny preview that makes a decision for you.

This is Officer Reynolds with the State Police. Are you the emergency contact for Michael Wilson?

Everything in me went still.

I excused myself and stepped into the hall.

“This is Barbara Wilson,” I said. “Is my son all right?”

“He’s safe,” the officer said quickly, a sentence every parent should hear before any other. “We picked him up at a casino over the state line. He wasn’t driving; a friend called us concerned he might try. He’s not under arrest. We’re asking that someone come get him. He listed you as his contact.”

I closed my eyes—grief, relief, a weary kind of gratitude that the worst sentence hadn’t been spoken.

“I’ll come,” I said. “Give me the address.”

I returned to the table with calm I did not feel.

“That was the State Police,” I said. “Michael needs a ride.”

Jennifer stood so fast her chair scraped. “I’ll go with you.”

Richard reached for his coat. “I’m driving,” he said. “You’re both running on fumes.”

The casino parking lot was a fluorescent no‑place of salt‑crusted cars and blinking lights. Officer Reynolds met us by the entrance—young, steady, the kind of professional kindness that feels like a hand on your back.

“He’s inside,” she said. “He’s embarrassed. He asked me to ask you not to make a scene.”

“We’re not here for a scene,” I said. “Just a son.”

Michael sat in a side office on a metal chair, hands clasped tight, eyes red. He stood when he saw us and looked at the ground like the linoleum might absolve him.

“I’m sorry,” he said, wrecked.

“You’re safe,” I said. “That’s what matters tonight.”

The ride home was quiet—Richard driving, Michael in the passenger seat, Jennifer and I in the back. The interstate unfurled in long dark ribbons. Tractor‑trailers breathed around us like patient beasts. Signs appeared—OAKRIDGE NEXT TWO EXITS, GAS 24 HOURS, HOSPITAL WITH AN ARROW POINTING TOWARD THE ONLY LIGHTS THAT STAY ON.

At my house, Michael stared at the snow‑glossed street.

“I called my sponsor,” he said. “Before I called you. I told him what happened.”

“What did he say?” I asked.

“‘I’ll see you in the morning.’ And, ‘Pick someone to tell the truth to tonight who loves you and won’t lie back.’” He shrugged. “So. You.”

“Thank you for telling the truth,” I said. “That’s the strongest thing you did all day.”

He nodded, jaw working like he was chewing glass.

“I hate this,” he said in a small voice. “I hate who I am here.”

“You’re learning who you are under it,” I said. “It’s going to hurt until it doesn’t.”

He finally looked at Jennifer. “I’m sorry,” he said. “For everything I said to you. For the mess I made of your name.”

Tears slipped down her cheeks. “I’m sorry for what I ignored,” she said. “But I’m not coming back into the fire.”

“I know,” he said. He meant it, at least for this minute.

Richard touched my elbow—a quiet reminder I wasn’t carrying this alone. “I’ll take you in at 8,” he told Michael. “There’s a meeting on Walnut.”

Michael nodded. “I’ll be ready.”

We parted in the cold like actors at the end of a hard scene—everyone drained, no one clapping. I watched Richard’s taillights disappear with Michael inside and stood for a long time on the porch, breath thick, robe wrapped tight, the neighborhood tucked under snow.

Inside, Jennifer and I sat at the kitchen table with mugs we didn’t drink. The heater kicked on. Somewhere, a branch scraped the roof like a gentle warning.

“What if this never ends?” she asked, voice thin.

“It will,” I said. “Not neatly. Not the way the movies do it. But it will.”

My phone chimed. A message from an unknown number.

Barbara, this is DeShawn. I’ve got Michael at the 7 a.m. coffee before the 8 a.m. meeting. You did the right thing bringing him home. I’ll keep you posted. One day at a time.

I showed Jennifer. She exhaled like a diver breaking the surface.

“Thank you,” she whispered to the room, to the man we didn’t know, to the small network of people who insist on being the net when someone falls.

Weeks later—how many exactly I couldn’t have told you—snow began to sink into the ground and the gutters sang with melt. Ellen and I ordered seed catalogs and circled things with a confidence that bordered on reckless: zinnias, sugar snap peas, climbing roses to Charles‑bridge the fence.

On a Thursday afternoon, I stepped out of the hospital into a hard, cold sun and saw Michael waiting by the door with a paper bag of bakery coffee and a look I hadn’t seen in years—undefended, honest.

“I signed the papers,” he said, handing me a cup. “For the house.”

I felt it in my knees first, the shock of a thing you begged the sky for and then forgot you had asked.

“We’re listing it,” he said. “Downsizing.” He swallowed. “It feels like failure and relief at the same time.”

“It feels like adulthood,” I said.

He nodded. “I don’t want to be the son who calls you only when I’ve broken something.”

“Then don’t,” I said. “Call me when the sky is ordinary and tell me about the clouds.”

He laughed; it broke and mended at once. “I can do that.”

That night, after I fed Ellen’s cat while she was out (a charmer named Bowie who pretended not to like me), I climbed into bed with Mary Oliver on the nightstand and the house quiet. I must have drifted for an hour before my phone vibrated on the pillow.

A single line lit the screen from a number I didn’t recognize, a sentence so simple it chilled me:

Check your porch.

I sat up, heart knocking. I turned on the lamp and listened—nothing but the heater and the midwinter pipes. I padded to the front door and peered through the peephole.

A small box sat on the mat—plain, brown, no markings.

I stood, hand on the deadbolt, and in that breath between fear and action, I realized something that pulled the room tight around me:

The handwriting on the taped label—the sharp, practiced script—was Thomas Parker’s.

…

I didn’t open the door.

I stood there with my hand on the deadbolt and looked through the peephole at a plain brown box with a label in steady, practiced script: Barbara Wilson. No return address.

Caution is a habit you learn in American hospitals and you keep it at home.

I texted Ellen: Are you awake?

Lights came on across the street. A second later: Always. Want backup?

Please, I wrote. And I called Richard.

“I’m two minutes away,” he said. “Don’t touch it.”

Ellen arrived first in her robe and snow boots, holding a flashlight the way a pioneer holds a lantern. Richard pulled up right behind her, hair tousled, coat thrown over scrubs.

“It’s probably harmless,” he said softly, “but we’ll be smart.” He tapped the box with his knuckle. No sound but the small thud of paper. He lifted it, felt the weight, and nodded. “Documents.”

I unlocked the door and stepped back. We set the box on the kitchen table under the bright overhead light that had seen every version of my life.

Richard slit the tape with a butter knife.

On top lay a letter in thick cream stationery.

Barbara,

I was wrong.

I owe you a public apology for the way I’ve spoken to you and the pressure I put on you in your own home. This will have to do for now.

Inside this box is what I should have brought you days ago: information, a plan, and money that is properly yours.

—T.P.

Under the letter: a cashier’s check paper‑clipped to an itemized statement. My name in the payee line. I brought the paper close to my reading glasses.

The check covered the home‑equity balance I’d paid, the early‑withdrawal penalties, and a tidy extra labeled “incidental costs.” My hand shook. Richard steadied the page for me.

“Keep breathing,” he murmured.

Beneath the check were three folders.

FOLDER A—Financial: credit‑freeze forms already filled with Jennifer’s basic info; a referral list for a nonprofit in Pittsburgh that helps families triage debt; a simple timeline created by a forensic bookkeeper—transactions, dates, accounts. It wasn’t an ambush. It was a map.

FOLDER B—Legal: a checklist from a family law firm in the city—what to gather, how to protect personal accounts, how to document communications; a draft letter offering Michael a voluntary financial separation agreement: no shared new debts; disclosure to a third‑party counselor; conditional support only if he entered treatment. Not a threat. A boundary written in legal ink.

FOLDER C—Health: three intake packets from reputable treatment programs in Pennsylvania and Ohio—two outpatient, one residential—each with a reserved evaluation slot “held” for a Michael Parker‑Wilson. A yellow sticky note in Thomas’s precise hand: Admissions can be transferred if he chooses a different center.

At the bottom of the box, wrapped like something fragile, lay a smaller envelope. Inside: a photograph I recognized from Jennifer’s wedding day—me in my best dress, Michael bending down to kiss my cheek, the Lake View water bright behind us. On the back, a single sentence in blue ink:

You have been family to us longer than I understood.

I sat down because my body told me to.

“Thomas sent this,” Ellen said, unnecessarily and kindly at once.

“Thomas sent this,” I repeated, as if saying it would help my history with him catch up to him now.

“What do you want to do?” Richard asked.

“Call Jennifer,” I said.

She answered on the first ring. “Is everything okay?”

“Better than okay,” I said, surprising myself. “There’s a box on my table we need you to see.”

She was at my door twenty minutes later in jeans and a sweater, snow in her hair. We went through the folders together. As she read her father’s letter, her face moved through an entire weather system and then settled in a place I hadn’t seen on her before: steadiness.

“My dad,” she said softly. “When he decides to fix something, he brings a truck.”

“We don’t need a truck,” I said. “We just need a map.”

Jennifer pressed her lips together and nodded, eyes bright. “Let’s follow it.”

We started with the least dramatic, most effective step: we each placed a credit freeze with the three major bureaus. It took twenty minutes and a cup of coffee. We scheduled a call with the nonprofit for the next morning. Jennifer texted her therapist for an earlier appointment. I emailed Martin to tell him about the check and asked how to document accepting it properly. Simple actions. Clean air.

At 9:00 p.m., my phone buzzed. A text from Thomas.

Is the box in your hands?

Yes. Thank you, I wrote. The check was not necessary.

It was, he wrote. It was due.

He added one more line: Michael called me. He asked for help. He says he will go to an evaluation.

Jennifer read over my shoulder, breath catching.

“Which center?” she typed from my phone.

Thomas replied: Any he chooses. First opening is Tuesday, 8 a.m., Lakeside.

Jennifer’s thumbs hovered, then tapped: Thank you, Dad.

A pause. Then: Thank Barbara.

We looked at each other and didn’t try to make words do more than they could.

Two days later the four of us—Thomas, Diana, Jennifer, and I—met at a quiet conference room at Lakeside Recovery, the one with the earliest intake. The administrator—a woman with calm eyes and a voice that could slow a river—walked us through the evaluation process. “He has to come in willing,” she said. “We can’t do this for him. But we can make the door easy to walk through.”

Michael arrived eight minutes late and gave me a look I knew when he was five and pretending not to be scared. He shook the administrator’s hand and sat where she pointed.

“I’m Michael,” he said.

The evaluation took an hour. When he came out, he looked both older and younger—like someone who had finally put down a bag he’d carried so long he had forgotten its weight.

“They recommend residential,” he said. “Thirty days.” He swallowed hard. “I said yes.”

Diana reached across the table and took his hand. Thomas stared at the paperwork as if his attention could hold the building steady.

“There’s an opening tomorrow,” the administrator said. “If you want to use the momentum.”

Michael nodded. He didn’t look at any of us. “Tomorrow.”

We drove home under a sky the color of pewter. At a stoplight, Michael spoke to the windshield.

“I don’t deserve any of this,” he said.

“That’s not how deserving works,” I said. “That’s how choosing works.”

He exhaled, a long, ragged sound. “I’ll try.”

“Try again,” I said gently, borrowing a line from a sponsor I hadn’t met yet. “And again after that.”

We spent the afternoon doing the quiet tasks that make a life easier to pick back up: a small bag with comfortable clothes, a list of phone numbers, a paperback mystery, a notebook. He handed me his phone and asked me to delete a handful of apps. When I finished, he stared at the blank spaces on the home screen like scars.

“I’ll call you from the landline,” he said, half a joke, half a vow.

Morning came clear and bitter. Richard drove us to the center because he understood about being steady on days that tilt. At check‑in, Michael hugged me with both arms like he hadn’t since college.

“I’m scared,” he whispered.

“I am, too,” I said. “We’ll both be brave anyway.”

He went through the doors and did not look back, which I decided to take as a kind of courage.

Outside, the wind cut down the long parking lot. Jennifer zipped her coat up to her chin and tucked her hands into her sleeves. Thomas and Diana stood together in a stillness that looked like prayer.

“Coffee?” Richard said, knowing there was nothing else to offer and offering it anyway.

We were halfway to the coffee shop when a notification flashed across Jennifer’s dashboard screen from the home‑security app no one had thought to silence.

FRONT DOOR—LAKE VIEW ESTATES: ACCESS AT 9:56 A.M.

We all stared at the time. 9:56 a.m. The same minute we had watched Michael walk through the Lakeside doors.

Jennifer tapped the thumbnail. The door camera filled the screen. A man in a black windbreaker took three steps up their porch and taped a bright notice to the glass.

“Is that…?” Diana said, voice catching.

Thomas leaned forward, jaw tight. “Posting,” he said. “Mortgage default.”

Jennifer drove the next block without breathing, then pulled to the curb under a bare maple and turned on the hazard lights.

No one spoke.

The tiny image on the screen showed sunlight flashing on the man’s plastic sleeve and the thick paper under it. He pressed the tape firm, knocked once, turned, and walked back down the steps into the bright, cold morning.

“I thought we had time,” Jennifer whispered.

“We do,” Thomas said, but his voice was sand. “Just not the time we wanted.”

“Drive,” I said softly. “Let’s go.”

Jennifer put the car in gear. The coffee would wait. The explanations would wait. We turned toward Lake View Estates—the neighborhood that had always felt like a stage set—and headed for a front door wearing a notice no one wants to see.

My phone buzzed in my pocket—an unknown number again—and for a long second I did not reach for it. Then I did.

Barbara, this is the mortgage servicer. We need to confirm who has authority to remove personal items from the property under the default timeline.

I looked up at the winter‑bright road, at the line of houses that had measured their value in square footage and lake views, and I understood what the next hours would be.

We were going to walk into that foyer together. We were going to take what was ours. We were going to leave the rest.

“Put them on speaker,” I said. “We’re five minutes away.”

…

The mortgage‑servicer rep came on speaker as we turned off the main road toward Lake View Estates.

“Thank you for calling back,” she said. “We need to confirm who has authority to remove personal items during the default timeline.”

Jennifer kept her eyes on the road. “I’m on the deed,” she said. “Jennifer Parker‑Wilson. My husband is Michael Parker‑Wilson. We’re cooperating. We need to retrieve clothing, documents, medications, sentimental items. No furniture or appliances.”

“That’s within policy,” the rep said. “We can email a 48‑hour access window. Someone will meet you to unlock and document with body cam. I’m sorry you’re going through this.”

“Thank you,” Jennifer said, and ended the call.

We drove through the stone entrance past a frozen fountain that looked like a sculpture on purpose. Lawns lay asleep under a crust of snow, and the lake beyond flashed cold and hard, a sheet of steel you could cut your eyes on.

At the house, a bright notice was taped to the glass. It said everything in black print that no family ever wants to read.

A security contractor in a dark jacket met us at the front walk. “I’ll record entry and exit,” he said, tone even. “Take your time. We’re here to keep everything aboveboard.”

Inside, the air smelled like cedar and lemon—the kind of staged clean you buy in bottles. The foyer’s double height felt like a church built to worship a kitchen island.

“We’ll start with documents,” I said. “Birth certificates, passports, insurance policies, tax folders.”

Jennifer nodded, already moving. “My files are in the office. Meds upstairs. Photos in the hall cabinet.”

Diana took the kitchen: “Pantry—two days of food to donate, the rest can stay.” Thomas opened a legal pad and made columns like a man who had learned the cost of not writing things down.

We worked in quiet. The contractor stood by the door, camera light winking, then turned politely aside to study the picture window as if he were there to admire the lake.

In Michael’s office, Jennifer opened a drawer and pulled out a rubber‑banded stack of envelopes. “Bank statements,” she said with steady hands. “And—” She paused. “Cards I didn’t know about.”

“Take only what you’re permitted,” I reminded gently. “Photograph the rest.” She nodded, snapped pictures, and left the cards in place.

Upstairs, I found the box with passports and Michael’s birth certificate exactly where Jennifer said it would be—in the linen closet on the top shelf, behind extra towels like a child’s version of hiding. My fingers brushed a smaller, old metal tin, the kind teachers used for lunch money. I slid it forward.

Inside: a folded index card, a key on a brass tag from a downtown bank, and a note in a hand I knew before I knew I knew it.

B—

If you ever need it. Box 317. Ask Martin to go with you.

—R.

It took me a heartbeat to realize R. was Robert. The scratch of his pen. The letter I’d seen on bills and Post‑its and birthday cards. The world narrowed to the size of a linen closet.

“Barbara?” Diana’s voice carried up the stairs. “Do you need help?”

“I’m okay,” I said, not fully convincing even to myself. “Found the passports.”

I tucked the key and note back into the tin, slid both into my tote, and carried the passports downstairs.

By the time I reached the kitchen, Thomas had packed a banker’s box with labeled folders Jennifer had pulled from the office: TAXES, INSURANCE, EMPLOYMENT, MEDICAL. Diana had filled two grocery bags for the community center pantry. Jennifer came down with a small jewelry box and a shoebox of photographs rescued from the hall cabinet—the childhood we had all lived in smaller rooms and honest light.

The contractor checked his watch. “You’ve got time,” he said, not unkindly. “No rush.”

“We’re finished,” Jennifer said. “One more closet and I’m done.”

She disappeared up the stairs and returned with a single coat and a small duffel. She looked around the house once, as if trying to see what to feel, and then looked at us instead.

“I’m ready,” she said.

“Let’s go,” Thomas answered.

On the drive back, the four of us were quiet in the practical way that follows work well done. The access window email arrived before we reached the main road. Thomas forwarded it to his attorney. Diana texted the nonprofit counselor to confirm tomorrow’s call.

At my house, Richard had left a casserole on the porch with a note in his blocky doctor handwriting: Eat this or I’ll write you up.

“An order,” Diana said, almost smiling. “From a man who knows compliance.”

We ate at my table off paper plates. The contractor’s body‑cam footage and the default notice faded at the edges for an hour while we passed green beans and good bread and breathed like people do when they remember food is allowed to taste like something even on hard days.

When they left, the winter light had gone thin and blue. I stood at the sink with my hands in warm water and the small metal tin on the counter.

Ask Martin to go with you.

I called his office and left a message: Found a key. Might be important. Can you meet me at First Federal on Main at nine tomorrow?

He texted back five minutes later: Yes.

That night I couldn’t sleep. I watched the digital clock blink through hours and listened to the house turn and sigh. At five‑thirty I gave up, made coffee, and sat at the table with the tin and a pen.

Dear Robert, I wrote, not because I expected an answer but because some conversations need a page. Thank you for leaving crumbs.

At 8:59 a.m., Martin and I walked into First Federal’s lobby where the carpet always looked new and a few customers held deposit slips like polite secrets. The manager checked our IDs, checked a ledger, disappeared, and returned with a small box that looked too humble to hold anything that could change a life.

In the viewing room, Martin set the box on the table and stepped back. “Your moment,” he said.

I lifted the lid. Inside were papers in Robert’s careful order: a letter; a folder of U.S. Savings Bonds I had forgotten we bought when Michael was small; an old CD certificate with interest that had quietly done its job; and at the bottom, under the folder, a sealed envelope with my name.

I broke the seal.

B—

If you’re opening this, it means the future didn’t look like we planned. I’m sorry for that. There’s enough here to help you steady yourself if things tilt. Please use it for you. If Michael needs help, give what you can without drowning.

I love you.

—R.

I put the letter down and pressed my hand over my mouth.

Martin skimmed the values, doing the math a lawyer’s brain does in emergencies and Tuesdays. “Barbara,” he said gently, “this is… meaningful. Conservative estimate, this plus the bonds gets you breathing room to retirement. More if you ladder the CD and let some sit. Robert did well by you.”

Tears came, quiet and clean. Relief is a form of grief you don’t recognize until it stands up in your chest.

“I thought I’d left myself with too little,” I said. “I thought I had made the last wrong turn.”

“You made loving turns,” he said. “This catches you.”

We signed what needed signing. The manager arranged to re‑issue the old instruments into something modern and useful. When we stepped back onto Main, the cold felt almost bright.

I called Richard.

“Good news?” he asked, answering on the first ring.

“Good enough to make coffee taste like a miracle,” I said.

“That’s the good kind,” he said. “Dinner to celebrate? My place?”

“Yes,” I said. “I owe you a story.”

In the days that followed, life found a new rhythm. Morning calls from the counselor. A standing Thursday at the community center pantry. Saturday coffee with Ellen under a heat lamp outside the bakery because winter was winter and friendship was friendship. Letters from Michael’s treatment center—monitored, handwritten, careful. He wrote about meetings and the way time worked when you measured it in honest hours. He wrote about missing his father’s watch and about seeing Robert’s face in the quiet between sessions.

He didn’t write about money. I took that as a good sign.

Two weeks in, Family Day arrived at Lakeside. The four of us sat in a circle—me, Jennifer, Thomas, Diana—on molded plastic chairs that knew heartbreak. A counselor with silver hair and kind eyes led the session.

“Family Day isn’t about blame,” she said. “It’s about naming. What happened. What we felt. What we need to recover—not just the person in treatment, but the whole system.”

Michael came in thinner, clearer. He sat, looked at his hands, then lifted his eyes.

“My name is Michael,” he said. “I’m here because I believed I could outthink the math. Because I learned to call panic ‘strategy.’ Because I hurt people I love and I told myself it was temporary. I’m sorry.”

We spoke in turn. Not speeches—sentences that carried their own weight: Jennifer’s fear; Diana’s regret for modeling the wrong gods; Thomas’s memory of a boyhood door taped with a notice; my exhaustion that had a name now.

The counselor nodded. “Amends are not apologies,” she said. “Amends are plans.”

Michael folded a paper. “I have one,” he said, voice steadying. “When I discharge, I’ll move into a sober‑living apartment near the center. I’ll sell the house with Jenny. We’ll split equity fairly under counsel. I’ll meet with a financial counselor weekly. I’ll give Mom a full accounting of every debt that touches her name. And—” He looked at me. “I’ll pay you back for the HELOC. Every dollar. It will take a long time. That’s the point.”

I opened my mouth to say he didn’t have to. The counselor lifted a hand and shook her head almost imperceptibly. I closed my mouth.

“Thank you,” I said instead. “I accept.”

On the drive home, Jennifer and I were quiet, then not. We talked about work—hers picking up, mine lighter and somehow larger. We talked about the way coffee tasted on hard days and the way small lights in small windows make a street look kind.

That evening, Richard made pasta with too much garlic and didn’t apologize. We ate at his kitchen island because life is funny. A year earlier, I’d have told you I disliked kitchen islands. Now I knew they could hold elbows and late‑night plans just fine.

He poured two small glasses of wine and raised his.

“To crumbs that lead home,” he said.

“To maps in metal tins,” I said.

We clinked and laughed, a laugh that felt like a door opening.

The next morning, Ellen texted a photo of tulip tips nosing through the frozen mulch in her front bed like the bravest scouts you ever saw. I sent her a picture of seed packets fanned out on my table—zinnias, snapdragons, basil—summer spelled in paper.

Then, because I had promised myself I would not hide inside survival, I bought two tickets to a chamber concert at the university and texted Richard: Saturday. You, me, Schubert, row H.

He replied: Dress or sweater?

I wrote: Dress for me. Sweater for you. We’ll look like a postcard.

The day before the concert, an envelope arrived by certified mail. Return address: Lake View Estates Homeowners Association.

I signed, thanked the mail carrier, and set it on the hall table. I told myself I would read it after lunch, after I checked on Ellen’s cat, after I sorted the pantry. I cleaned the sink. I folded a towel. I opened the envelope.

Inside was a letter on thick paper and a photograph. The letter was formal, cold, informing us of fines assessed for landscaping violations, exterior decor “not in compliance,” and a final demand for payment—fees that had multiplied in the absence of attention. The photograph showed our front lawn under summer sun with a tiny corner of something familiar peeking from the flower bed—blue metal, scuffed, as if someone had half‑buried a lunch‑money tin near the hydrangeas.

My heart knocked once in that way it does when the body knows a thing before the mind does.

The letter slid from my fingers onto the table.

If there was one blue tin in the linen closet, what was this in the ground?

I looked at the date on the photo: July, the year after Robert died. The key on my counter winked in the winter light as if it knew a secret and was willing to tell it.

I picked up my phone and typed three names into a group thread: Jennifer. Thomas. Martin.

Found something. In the HOA photo. Front bed. Looks like another tin. Can we meet at the house during the access window with a witness present?

Three dots appeared from all three corners of my life at once.

Yes, Jennifer wrote.

I’ll bring a small spade and a large thermos, Thomas wrote.

I’ll bring the law, Martin wrote.

I stood in my hallway with the winter sun on the floorboards and felt the story lean toward something I hadn’t expected—another box, another note, another turn in a life that had already turned more than I thought it could.

“Alright, Robert,” I said to the empty house. “Show me where you left the rest.”

…

We met at the house at ten sharp, breath fogging in the January cold, the lake a sheet of hammered glass beyond the pines. The access‑window email was printed and clipped to Thomas’s legal pad. A representative from the servicer stood at the walk with a small body cam and a clipboard. Martin wore his courthouse coat, the one with deep pockets for pens and answers.

Jennifer pointed to the HOA photo in her hand. “Front bed,” she said. “Left of the hydrangeas. That blue.”

Thomas knelt first because fathers do things like that even when the children are grown. He pushed aside the brittle lace of last season’s mulch with a gloved hand. A flash of paint winked up from the earth. He used a small spade he’d brought “for leaves,” which was diplomatic for what all of us knew he’d hoped to find.

The tin came up whole—dented at the corners, scuffed, intact. The contractor’s camera light blinked its little red eye. We all stood very still.

“Kitchen,” Martin said calmly. “Flat surface. Good light.”

We moved like a procession through rooms that had been a stage and now were just rooms. On the island, Thomas set the tin on a folded towel. Jennifer breathed out and in, out and in. I slid my reading glasses into place. Martin popped the old latch with the side of a butter knife.

Inside: a manila envelope, a Ziploc bag, and a note in Robert’s hand.

B—

If you found the first, you’ll find this. This one’s for the house if we ever needed a ramp off a burning bridge.

The manila envelope held copies of statements I’d never seen—small municipal bonds in Barbara Wilson’s name, purchased slowly in the years after Robert’s promotion, the kind of safe, unflashy things you buy when you intend to keep promises. The Ziploc bag held a flash drive labeled in tidy block letters: MAPLE TRUST—FINAL.

Martin plugged the drive into his laptop and opened a single PDF with the patience of a person who does not hurry the moments that change a family. The document was a trust amendment from a decade ago, properly notarized and filed, that I had somehow missed in the paper flood of those years. It named me as trustee of a modest but real fund intended “for Barbara’s housing security and long‑term care,” with a clause that allowed emergency use “in the event of unforeseen financial distress related to family obligations.”

At the end of the file, there was an addendum—simple and unmistakable.

In the event of the sale of any primary residence after my death, proceeds allocated to Barbara first until her housing is secure.

—Robert Wilson.

I stared at the line and felt the ground of the last months tilt back toward level by a notch I hadn’t believed possible.

Jennifer was the first to speak. “We’ll honor it,” she said, clear and immediate, before Thomas or Martin could turn it into a meeting. “When the house sells, you are made whole first. Dad?”

Thomas nodded once, jaw set in the way of a man who has learned the clean economy of yes. “We’ll coordinate with counsel and the servicer to structure the sale.” He looked at me. “We’ll do it right.”

The servicer rep—kindness in a navy jacket—cleared his throat without intruding. “I can note intent to sell and start a cooperative timeline. It often helps.”

“Please do,” Martin said. “We’ll submit the paperwork within five business days.”

We signed nothing that day and everything that mattered anyway—agreements said aloud at a kitchen island under winter light. When we stepped back outside, the lake had softened where sun touched it. It would freeze again before spring, but for now, it looked like water.

Michael finished his thirty days at Lakeside and stepped into a sober‑living apartment that smelled like laundry soap and second chances. He carried a duffel, a spiral notebook, a paperback with the spine broken in the middle. DeShawn met him at the curb and clapped him on the shoulder like good teammates do.

His amends came in sentences and spreadsheets. He sat with Martin and me at my table and read from a paper he had written by hand because typing felt too quick.

“I will pay the HELOC back to you in monthly installments starting the day I receive my first paycheck after rehire,” he said. “It will take years. That’s the point.” He looked up. “I will send you a weekly accounting of my expenses for a year. I will keep a zero‑balance card for emergencies only, and you will have read‑only access. I will not ask you for money. If I slip, I will tell you before anyone else can.”

“You’ll tell DeShawn first,” I said, and he nodded. We signed the plan and stuck it to the fridge with a magnet shaped like Ohio someone gave me at a nurses’ conference.

He and Jennifer met with the real‑estate attorney and the servicer. They listed the house at a fair price. The first offer was insulting; they declined it without drama. The second was solid; they accepted contingent on a clean timeline. Lake View Estates shrugged in the way neighborhoods shrug when a story ends that they thought would go on forever. The frozen fountain began to run again in March.

On a Tuesday in April, we closed. The proceeds did what Robert had intended: retired the last shadows of debt tied to my name, funded a down payment for the next small, sunlit chapter, and tucked a cushion under the chair of my retirement so it no longer wobbled.